They were once hallowed spaces of knowledge. Today derelict and with aging collections of books, libraries in the city still hold secrets within their cavernous halls.

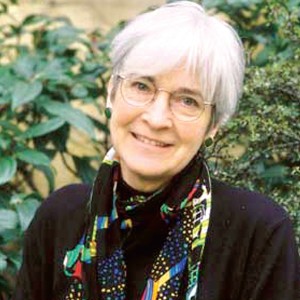

There’s pin-drop silence. The gentle whirr of a fan, the rustle of paper, and the thud of a dropped book often cracks it. Unlike in school libraries, there are no ‘shushers’. There isn’t need for one; there aren’t many visitors to shush. A few of the city’s grand old libraries, for most part of the day, are left with just the aging books. Pick one from the shelf, amidst a cloud of dust, and you’ll see tiny silver fish play hide and seek. Many of them, difficult to maintain, have been brutally shredded in the past, says Uma Maheshwari, librarian at Madras Literary Society (MLS) — the oldest in the city. But not anymore. People are now adopting books — paying all it takes to get them back in form. These sit on a separate shelf, newly-bound and way past their lifespan. “We have given them a grace life of 200 years for now,” says Uma, drumming her fingers on the remaining 45, which await adoption.

Braving vertigo

Madras Literary Society

“Books can be taken from there, but then most do not, because of the dust,” shouts Uma Maheshwari from below, as I carefully climb the metal ladder leading up to a set of shelves. “We should probably install a chair lift…” she says, before turning away to attend to an elderly visitor, who wants a certain book about writings by (Jawaharlal) Nehru. The search begins. The books are not classified; catalogues not set in order. After the renovation of the 203-year-old red-brick structure a few years ago, the wiring has been detached, and the books moved from their places. Founded in 1812, the Society was part of the College of Fort St. George, started by the then collector of Madras Francis Whyte Ellis. In 1830, the Society became an auxiliary of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain, and functioned out of Connemara Public Library, before moving to its current location on College Road, inside the Directorate of Public Instruction complex, in 1905. “We need volunteers to dust, classify and set them all (around 80,000) up again,” says Uma, leaning on an antique rosewood chair. Clutching the shaky railing, I take another flight of steps. From here, the thick layer of dust on the fan and on the cupboards is visible.

So are the brick-and-lime mortar walls and tall windows with Rajasthani accents. Looking down through the grill gets me a little dizzy. “So when is the lift due?” I ask.

Home to: Arretolis Opera Omania QVAE Extant Graece and Latine (1619), Travels in India by John Baptista (1680) and Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica by Isaac Newton (1740)

Coffee with Captain G.A. Mustafa

Mohammeddan library

From inside a glass cubicle, an elderly man asks for my business card and tells me to write my address and contact number in a visitor’s register. Retired Air India commander Captain G.A. Mustafa’s family, starting with his great grandfather, has been taking care of the library ever since it was established in 1850. According to the book Madras Rediscovered by chronicler S. Muthiah, ‘the library was started as Madras Muslim Public Library by Surgeon Edward Green Balfour, head of the Museum, and his sponsor, Nawab Ghulam Mohammad Ghouse Khan of Arcot.’ Mustafa was there during the critical period between 1939 and 1945, when the library lost much of its collection; and when the building, which boasted Islamic architecture, was pulled down in 1996, and reconstructed in 2005. “There are over 15,000 books and manuscripts, many gifted by the kings of Egypt, Turkey and Jeddah in the 1850s. They cannot be found anywhere else in the world,” chips in librarian Tameemur Rahman.

It’s around 5.30 p.m., almost closing time. Hot cups of coffee are brought in. An 1852 edition of a yellowing astronomy Persian book in one hand and a freshly-bound book in another, Tameemur gets technical about photo encapsulation — a technique to document manuscripts using specially processed polyester film coated with glue — which he claims was kickstarted in the library.

On my way out, Mustafa stops me and says, “Saba Mustafa is my wife.” There is a long pause. “She was the one instrumental in getting the library back in shape. Will you please mention that?”

Home to: H.D. Love’s Vestiges of Old Madras (100 years old), The Lancet magazine (July 1883),Ramayana written in Persian, and the Bible of Barnabas

Walking in the dark

Connemara Library

On the first floor of Egmore Museum Library, at the far end of the room, a faded poster reads: ‘Way to the old building’. The narrow path leads into a bright circular room with desks and tables, and a staff member who takes your reference requests — just like in a departmental store. That is the closest you can get to the Connemara Library (established in 1890 by Bobby Robert Bourke Connemara) — unless you have special permission to visit.

It’s 15 minutes to 5 p.m. — closing time. I walk down the red-carpeted floor to a mammoth structure with an array of teak wood shelves. To my right is a glass case with important books like Thambiran Vanakkam by Henriques (the original copy of which rests in London); bang in the middle is a Gandhi statue by Roy Chowdhury; and on the floor are old maps of the Tamil Nadu villages, laid out like tiny step mats. I open one to see a dark sketch of Kulavoipatti village in Pudukottai district. To my left is a counter with a small window, from where the librarian used to issue books back in the day. A narrow wooden staircase leads to a long wide hall spread with books that have been left to dry on the floor. The other end includes large circular reading desks. Connecting both is a small space with shelves that house records of Lok Sabha debates. As I pick up a book, the lights snap. It’s spooky, but only for a while. The colourful Burmese windows let in soft shades of light, just enough for me to see the truncated semi-circle roof and the ornamental acanthus leaves and flowers adorning the pillars, marble-floors, and the exit.

Home to: Omnes Quae Extant by D. Hieronymi Strido (1553) and Opera Quae Exlast Ominia (Greek Latin) by Plato (1578) are part of the nearly eight lakh books.

Smelling lemongrass

Oriental Manuscripts Library

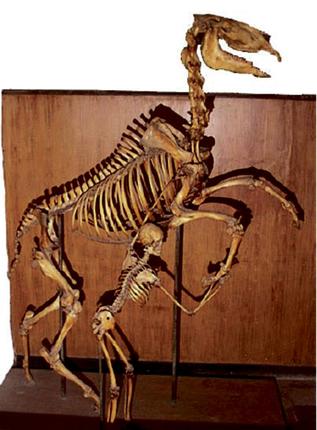

Librarian R. Chandramohan carefully unlocks a glass panel inside a room with double doors to take out a lingam-shaped structure. “This is the original text of the Thiruvasagam written by Manikavasagar,” he says. The over-350-year-old palm manuscript was showcased at the World Manuscripts exhibition in Frankfurt, Germany, a few years ago, he says. Next, he takes a set of palm leaves which have the famousThirumurugatrupadai by Nakkeeran inscribed on them. Right next to it is The New Testament in Hebrew, Soolini Manthiram, Mahabharata drawings on handmade paper, and an ivory manuscript case. “There is more,” he says, opening the door to rows of wooden shelves with compartments filled with over 70,000 manuscripts in Tamil, Sanskrit, Telugu, Kannada, Marathi, Urdu, Arabic and Persian; and air thick with the smell of lemongrass. A few palm leaves, freshly anointed with the oil, are spread on the floor. Most of these are personal collections of Colonel Colin Mackenzie (who came to India in 1783 as a Cadet of Engineers on the Madras Establishment of the East India Company), linguist and traveller Dr. Leyden, who was in India between 1803 and 1811, and C.P. Brown who was part of the Indian Civil Service in the 1830s, Chandramohan reads out from a presentation. The library, which is controlled by the Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamil Nadu, was established in 1869 with the collection which was first housed in Presidency College, before moving to Madras University. Locking the door behind him, he says, “Even if you go out of this room, the memory of the smell will linger.” Ten minutes later, I realise he was right.

Home to: Tolkappiyam, Manimegalai, Silapathikaram

Meeting the grandfather of Tamil

U Ve Swaminatha Iyer Library

The security at the Kalakshetra Colony gate says “Go right ahead”, and sure enough, hidden behind the trees, is a white building. A statue of U Ve Swaminatha Iyer, the grandfather of Tamil, welcomes visitors. Only, there are none inside. Just staff members, who are on their lunch break. The library, which was established in 1943, includes Tamil literature collected by UVS, who is known to have spent his life searching for palm leaf manuscripts and transcribing them into books. This content has now been converted into microfilms (462 in total) by Indira Gandhi National Arts Centre; and these have in turn been converted into DVDs. The library in itself is being computerised with research facilities; it clearly seems to know the road ahead.

Home to: 69 of the 96 palm-leaf manuscripts of Sangam literature; 32 of the surviving 120Tolkappiyam palm-leaf manuscripts.

In pursuit of art

DakshinaChitra Library

After catching a show at the Kadambari art gallery, I head to what is probably DakshinaChitra’s best-kept secret. Serpentine queues of children walk in and out of the heritage houses, and a significant crowd waits to get their hands messy at the ceramic art centre. But the library seems withdrawn from the buzz. The library started at Madras Craft Foundation office in 1984 with around 200 books, now has over 9,000, apart from the 5,000 volumes that are National Folklore Support Centre’s collections. With out-of-print art books and journals like Indian Magazine, Lalit Kala, Indian textile history and Marg, and around 1,50,000 photographs, the place seems like an extension of the gallery.

Home to: Traditional Indian theatre, UMI’s dissertation on Therukoothu, Theyyam and Tolubommalata, Sargam; Thurston’s volumes on Castes and Tribes of Southern India

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus / by Naveena Vijayan / Chennai – March 11th, 2016