Kannerimukku is where John Sullivan fell in love with the hills and discovered Ooty, writes SUBHA J RAO

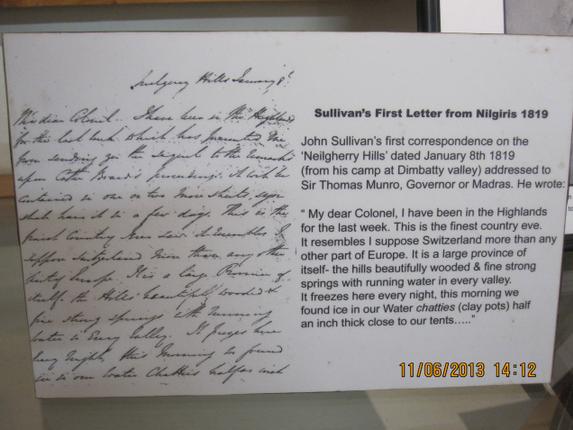

January 8, 1819, Dimbatty Valley. Sitting in a valley kissed by the clouds, Collector of Coimbatore, John Sullivan, 31, wrote to Sir Thomas Munro, Governor of Madras: “My dear Colonel, I have been in the Highlands for the last week. This is the finest country… it resembles I suppose Switzerland more than any other part of Europe… it freezes here every night, this morning we found ice in our Water chatties (clay pots).”

Nearly two centuries later, the valley still retains part of the charm that captivated Sullivan, who went on to found Ooty, the first hill station in India. On a wet June afternoon, the tea plantations and vegetable patches shimmer a bright green. In a way, they are a tribute to Sullivan. For, it was he who introduced European fruit trees, vegetables and flowers to the hills and suggested that the British cultivate tea there.

When he first trekked up the Neilgherry (as the Nilgiris were then known) with a contingent of soldiers, elephants and ponies (who were disbanded halfway), it was through dense shola-filled forests and steep cliffs. During his second visit to Dimbatty (which means soft, pillow like) valley, Sullivan set up a camp. Later, it became a two-storey structure called Pethakal bungalow, named after a sacred stone that existed there. Sullivan lived there till 1823. In the five-acre property, he experimented with cultivation of potato and other English vegetables such as cabbage, beetroot and carrot. In the 1820s, the spud finally made its appearance in Ooty.

Today, the area is called Kannerimukku. You drive past winding roads, mist-soaked mountains, tea factories and tiled houses to reach the memorial, resplendent in brick red against a sea of green. When Dharmalingam Venugopal, director of the John Sullivan Memorial and Nilgiri History Museum (now housed in the Memorial), first saw it, it was crumbling, a pale shadow of the edifice it once was. In the years leading to its ruin, it was ironically used to store hay and the very potato that Sullivan introduced!

Today, with Government funds (the Hill Area Development Programme) and private donations, it stands two-storeys tall; the rooms hold a treasure trove of material about Sullivan and his family, the role of the British in the Nilgiris and the traditions of the local tribes.

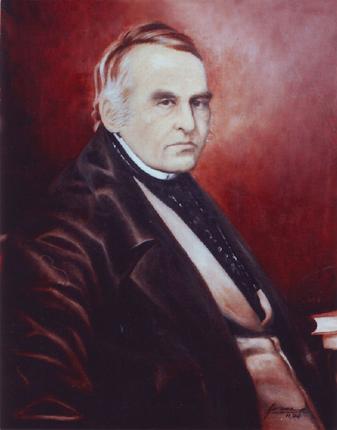

There’s an original pencil sketch of John Sullivan, drawn when he was a lad of 15, before he set out for India. It was donated by historian and writer, David Sullivan, his great great-grandson.

There are also some exhibits collected by Venugopal that show you what life in the hills used to be like. A Badaga wooden food plate polished with use, hunting tools of local tribes, the bugiri, a cane flute used by communities in the Nilgiris, photographs of the local tribes by the self-taught Philo Hiruthayanath….

The section on the modes of communication and transportation in the hills is an eye-opener. The Nilgiris had six entry points (Sispara Ghat, Mulli, Gudalur, Sigur, Coonoor and Kotagiri) at a time when most hill stations had two. Today, five remain open; the original Sispara Ghat that connected it to Calicut has been closed. And, how did people travel? By foot, horseback, palanquin and tonga.

Though the Memorial is located just two km off Kotagiri, this is not a road regular tourists tread. But, there’s every reason why they should. Because, this is where it all began, years ago on a cold January day.

(June 15 marks John Sullivan’s 225th birth anniversary. The Nilgiri Documentation Centre, which works out of Sullivan Memorial, organises a two-day trek on June 15 and 16 to retrace the Sullivan trail.)

Getting there

Drive up to Kotagiri, about 75 km from Coimbatore. Take the road leading to Ooty. The memorial is two km from Kotagiri, past Ramchand Square and Kotagiri Medical Fellowship.

What to do

Read the well-documented panels at the memorial (http://www.sullivanmemorial.org/) that throw the spotlight on the making of a hill station.

Browse through the books on the Nilgiris that Venugopal has collected.

Visit the Ooty lake, created by Sullivan, and Stonehouse, where he lived. It now houses the Government Arts College. Plan a trip to St. Stephen’s Church, Ooty, where Sullivan’s wife Henrietta and eldest daughter Harriet are buried.

Where to stay

Kotagiri has many good hotels and homestays. Else, stay in Ooty (32 km) and drive down to the Memorial on your way back to the plains.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Feature> MetroPlus> Travel / by Subha J Rao / June 13th, 2013