Insights into bringing a story alive on stage, the power of imagination and words, reinventing mythology and the eternal intensity of compelling photographs mark Anusha Parthasarathy’s account of the Fest

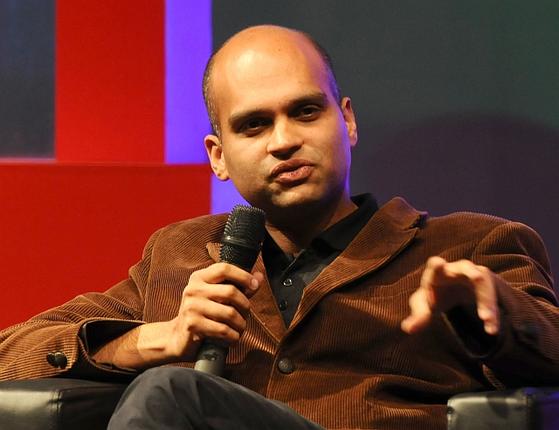

Aravind Adiga

The evolution of a writer who was born in a hospital near Poonamallee High Road and grew up in a house nearby into a Man Booker prize-winning author is the story of Aravind Adiga. In his conversation with David Godwin at The Hindu Lit For Life 2014, Adiga talked much about the city of his childhood and the good memories of the train journeys from Mangalore to Chennai. “But my childhood was dominated by the Udupi hotels of Madras,” he said. “Especially Woodlands and Dasaprakash. For a long time, I looked for a Dasaprakash hotel wherever I went.

When David brought up The White Tiger and the story behind it, Aravind recollected seeing a magazine a driver of his colleague was reading in New Delhi once. “It was called Murder and this pulp fiction was a rage among the drivers of New Delhi. It had a collection of stories where the driver kills his owner,” he explained. “In India, the middle-class takes a lot for granted. The domestic help is privy to a lot of personal information. I wanted to ask the question, why is India safe? The core of the novel, of course, is about how a man becomes free.”

Aravind’s first novel was set in New Delhi and the second in Mumbai (Last Man In Tower). He is working on his third. “The Madras I grew up in is gone, and for a long time, I was looking for my childhood. I understand now that I must look at the future. I have now decided to learn Tamil,” he said. When asked if the function of literature was not to recover the past, he said, “In the book The Leopard, there is a line that goes ‘Everything must change so that everything can stay the same’, and I think Chennai has done just that. You don’t always have to write about a place you enjoy,” he said.

From Page To Stage

Everyone sat in a huddle, eyes flitting between the screen and the speaker at the From Page To Stage: Bringing A Story Alive, a workshop by Nikhila Kesavan. The actor-director spoke in length about adapting short stories and works of fiction into stage productions or feature films.

The workshop dealt with two novels; one that had many characters and the other that was a monologue. “A novel rarely lends itself to stage. And there are so many places, a hostel, cafe or a terrace. How do you show so many things for a stage production? This is where the director decides which actors are most important and who can be avoided,” she said. And on the subject of the play or movie being compared to the book, she said, “There will always be comparisons when you have an adaption. But it’s best not to be too aware of it. I just evaluate the whole play as a piece of theatre.”

There is no one formula to successfully adapt a novel or a story, and everyone has to find their own way, the actor pointed out. “Sometimes, a book has so many incidents that if you take out even one, the story will fall apart. In other books, there is a lot of talking and only two or three incredibly dramatic scenes, but they are so good that you want to adapt the story. There are different ways of treating the stories — you have monologues or you could divide the passages among many voices so it’s not boring.”

Nikhila also added that it was easy to point out from the first reading if a play was meant for theatre. Sometimes, a play might make a great film but fail on stage. “There are many challenges to tackle in theatre. If you are making a movie, you think as a director, actor and writer, which is different from a playwright writing a script.” And on perspective in an adaptation, she said, “Many people have seen different versions of The Ramayan, but what do you see in the text? It’s how you portray and design the story. Your characters can be very radical and different from the original or it could be a good retelling,” she explained.

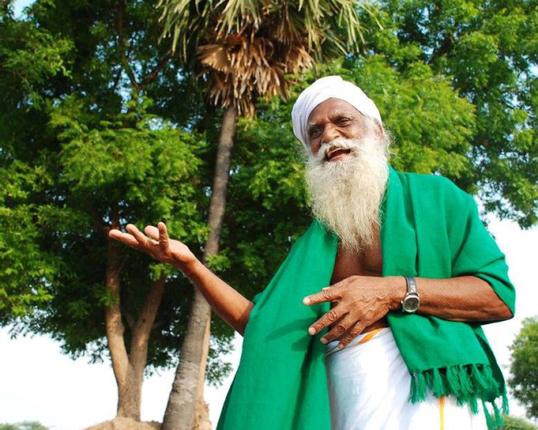

Evolution Of The Imaginary

From the multiplicity of perspective to the loss of poetry and handling of colours on screen, noted filmmaker Kumar Shahani explained the concepts of the imaginary through his experiments in films, conversations with intellectuals all over the world and his views on the changing state of imagination in India and overseas. He was introduced by arts editor Sadanand Menon.

The session began with a frame that inspired a scene in his film Khayal Gaatha, which looked at the history of Khayal singing. He talked about the different perspectives that can be captured on one frame. “I worked with the idea of multiple duration — being present simultaneously and how the place around it gets changed. And how the resonance around an area changes,” he said. The painting was of a woman peeping out of the window, looking at a lover. At the far end, another conversation takes place.

Shahani spoke of the perils of fitting into a category. “When I presented this painting in Sydney, many didn’t understand what I had done with it. They have blocked out all other kinds of enunciation because they are so influenced by the revolutionary thinking of Da Vinci or other thinkers,” he said.

The filmmaker also spoke about the importance of colour, how to handle it and the role technology has played in changing perspectives. “I’m appalled by the attention span of the breaking-news genre or Hollywood, where you can’t really look at anything,” he explained. “I see a future where the less opportunities we are given to create, the more we use other people’s creations (which they created for their own purpose).” Sadanand added that image is a form of consciousness. “When you can imagine an image, it’s a whole new consciousness that is emerging depending on how the creator re-imagines it. The imaginary is not fiction, but a world in the process of becoming real.”

Making Waves

With two MBA graduates-turned-authors and a literary fiction writer on the panel, the discussion Making Waves: How To Create An Impact As A Writer dealt with many interesting issues such as how important marketing is to make a book sell in today’s scenario, how different is it for different genres of books, and how one views literary fiction or commercial fiction today. The lively discussion among Anita Nair, Ashwin Sanghi and Ravi Subramanian was moderated by Naresh Fernandes.

“It’s difficult to construct a Chinese wall between the two lives I lead — I use business tools in writing. The amount of time and energy one would devote to a business plan, I would dedicate to a plot,” said Ashwin Sanghi, known for best sellers such as Chanakya’s Chant and The Krishna Key. He believes the author’s work does not stop with writing.

Banker-author Ravi Subramanian agreed. “When you write a book, there are enough people to read it. But how do you reach the right audience? So I send out my manuscripts to a few trusted people I’ve interacted with. They are people with no connection to banking. I do this so that I can change the script in case there are parts of the book they don’t understand. It also helps improve the story.”

Anita Nair’s rule is to write books that she likes to read. “They seem to endure,” she added. “Writing, to me, is an intense and personal exercise. I don’t see the reader in my mind. I don’t believe marketing is important. The book has to be good, only then will it endure. You needn’t be aggressive. A book is not a product.” Ravi explained the need for an author to become the CEO of his book. “A lot of good books don’t make it because readers don’t know they exist. An author must take charge of everything from writing to marketing the book to make sure the reader sees it.”

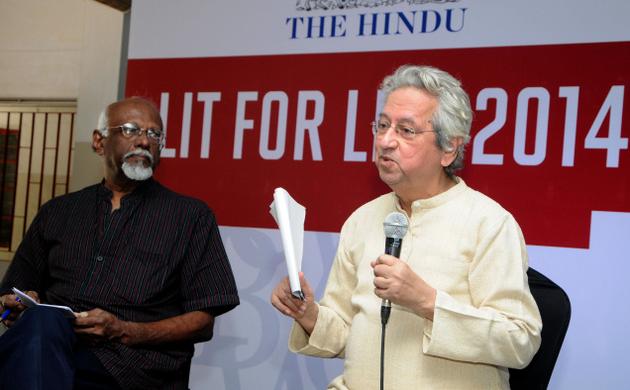

Reinventing Mythology

Are mythological retellings relevant? How does inventing mythological texts help us contend with the present and the future? These important questions and more were discussed in Revinventing Mythology: The Art Of Rewriting Religious Narratives. The panel had Paul Zacharia, Veenapani Chawla and A.R. Venkatachalapathy, and was moderated by K. Satchidanandan.

The moderator began the session by pointing out that every field was in some way impacted by mythology and that they had become a part of everyday life. “Now Ekalavya is being seen as a big protagonist in Dalit literature. Shambuka is another figure who is gaining prominence; Rama is being questioned on killing him and Vaali. Rama is being questioned on ousting Sita from the kingdom. This is because myths are polyphonic and can be interpreted in many ways and contexts,” he said.

Paul, a short story writer and columnist, talked about confronting one’s religious beliefs through reinvention. “It was an attempt to reinvent myself spiritually so that I could enjoy inner freedom,” he said. Veena, an actor, director, choreographer and composer has done extensive work with mythology and talked about the importance of three characters in epics — Ardhanarishwar, Sabyasachi and Brihanalla. “They are concepts, ways of viewing humanity. Ardhanarishwar brings together two polarities in gender. Sabyasachi brings together the capacities for knowing in different ways. The middle ground or the third side to these two characters is Brihanalla, which not just combines two different genders but also the capacities.”

A.R. Venkatachalapathy brought up the issue of myths helping one contend with the past, present and future. “When a society is modernised, contending with myths is considered as a way of being modern,” he said. “There have been retellings with Ravana as the hero of the epic or with Hiranya Kashipu. Here the retellings don’t reject the myth, but rather rewrite it in a different way.”

Remembering Bhopal

It has been 30 years, and yet, the images that Pablo Bartholomew shows on the screen continue to hurt as much as they did when they were first taken in 1984. Introduced by Rahul Pandita, the award-winning photographer narrated his experiences in Bhopal during the time of the gas tragedy through his unforgettable images.

Pablo began his photo presentation with pictures of himself as a child and a young man, talking about his father who introduced him to photography. He then showed snapshots from his early work, recording the hippy culture of students at that time. “Many of them are parents now and their children are unable to accept how hip their parents were back then,” he laughs. In the collection was a picture of the Rock Fest in St. Stephen’s College in 1974. There were also pictures of Satyajit Ray on the sets of Shatranj Ke Ki Khilari.

In 1983-1984, Pablo took to news photography and shot many images of Operation Blue Star and the riots that followed. When the Bhopal gas tragedy took place, he rushed there and landed three days later. The images of J.P. Nagar, men wearing scarves around their noses and mouths, people sporting glasses to shield their eyes, are haunting. There are more and more pictures of hospitals, doctors checking patients, dead livestock, mass burials and so on. The most haunting image, which won him the World Press Photo of the Year, is of an infant being buried and a hand reaching out to caress. Pablo visited Bhopal many times afterward, on the first, ninth, 10th and 20th anniversary to document whatever changes have happened. “Memorials have been erected for those who died and more people are agitated and getting on the streets,” he said. He promised to visit Bhopal again soon.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus / by Anusha Parthasarathy / Chennai – January 15th, 2014