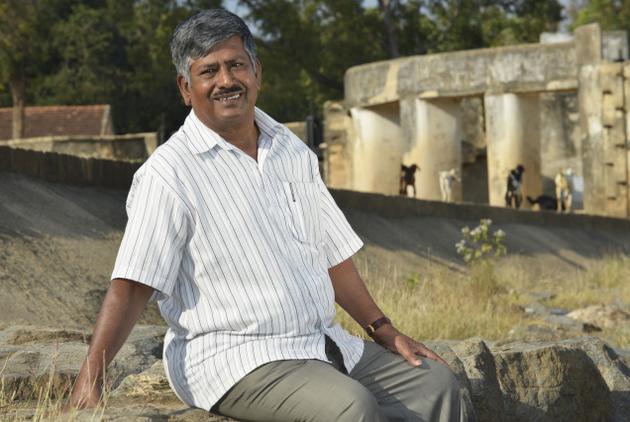

An archaeological dig at his grandfather’s farm set off an insatiable thirst in K. Jayaraman for the past

Perur K. Jayaraman was a school boy when his interest in history was piqued. He remembers the excitement: “While digging a pit to plant a coconut tree, we found a flat slab inside. It had a side wall and a centre compartment that contained Mudumakkal Thaazhis ( burial urns). We also found agal vilakkus, jaadis, knives, small gold coins and a sunnaambu container. People called it pandia kuzhi, a derivative of pandaya (old) kuzhi”. This discovery led to the Archeological Survey of India conducting an excavation.

Kovai Kizhar C.M. Ramachandra Chettiar, Coimbatore’s first historian, recorded the findings in his book Kongunaatu Varalaaru . But he did not mention the name of the owner of the farm (Jayaraman’s grandfather). When the school boy asked him why, Kovai Kizhar gave him a sukku mittaai and told him that history cannot be written that way as the farm may belong to someone else later. “I realised the truth of his statement much later, but this conversation was the starting point of my interest in history.”

Today, at 64, Jayaraman is still fascinated by the topic. “History is always about kings and their battles. What about our soil and its people?” he asks. “It’s time historians popularised soil, people, nature, hills and rivers. We have to leave the knowledge behind for the future generation.”

Armed with books such as The Ancient Geography of the Kongu Country and Coimbatore Maavattathu Kalvettugal, Jayaraman set out to unearth history. “It was a fascinating learning experience. Along with Dr. R. Poongundran of State Archaeology Department, we discovered hidden treasures at Perur, Vellalore, Kodumanal, Noyyal basin, Muttam, Narasipuram, and cave paintings at Kumittipathi. Vellalore in Coimbatore thrived as a trade hub. We discovered the 1,000-year-old Muthuvaazhiamman temple near Alandurai. The deity sculpted on the lines of Madurai Meenakshi takes your breath away. Did you know that there is a Thooku Mara Thottam near Udumalpet, which used to be for execution? People were also thrown off a hill top near Anaimalai as punishment,” he narrates.

He says Coimbatore’s multi-cultural, multi-lingual influences dates back to the reign of the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyas, the Naickers, Mysore Maharajas, Muslim rulers and the British.

The discovery of the Rajakesari Peruvazhi near Kovaipudur was memorable, he says. “It’s a trade route that connects the Bay of Bengal with the Arabian Sea via Vellalore. It was the cow herd boys in the locality who first spotted it. A kalvettu (inscription in stone) there carries a thanks-giving poem where the traders thank the Raja for giving them nizhal (shade or protection). Those days, a nizhal padai followed the travellers to protect them and their goods from burglars. I took a group of school students to the Peruvazhi site and they performed a play at the spot and brought alive history and the stories I told them.”

Jayaraman speaks of the cave painting of Kumittipathi with amazement. “The paintings of people on elephants, chariots, deer and peacocks, and other geometric shapes are over 3000 years old but are as good as new even today!”

His introduction to Tamil literature also started from his farm located behind the Perur Tamil College. Pulamai Piththan, Kuppuraasu, Puviarasu and Rasiannan engaged in debates and discussions of Tamil literature as they bathed in his farm. Hooked by their conversations Jayaraman devoured books on Tamil literature.

Sharing information

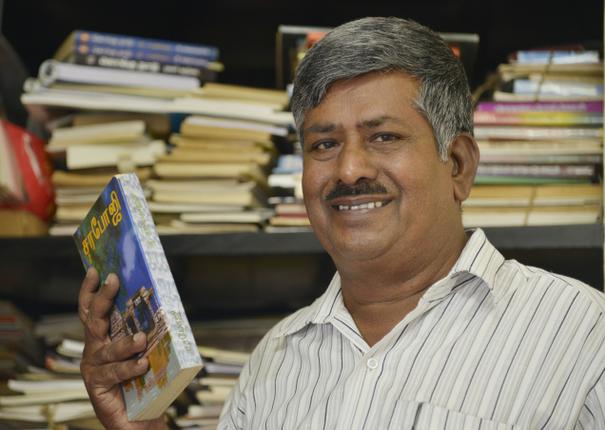

Jayaraman’s knowledge of the environment, heritage and Tamil literature, has made him a valuable resource person. NGOs, research scholars, and students flock to him for information. He has contributed to many books too such as C.R. Elangovan’s Coimbatore Oru Varalaaru and Cbe Cyclopedia.

Jayaraman fondly recalls famous people who have hitched a ride on his moped! “Once Medha Patkar and I rode till the reserve forest in Anaikatty,” he remembers. He also took Sunderlal Bahugana around the forests of the Western Ghats. “The first question Bahuguna asked the forest officers was — ‘How many more tress have you spared?’ and they didn’t have an answer.” Jayaram was also close to organic farming scientist Nammalvar who passed away recently.

Destroying Nature for development was unsustainable, says Jayaram. “Car irukkum aana sor irukkadhu. We had over 40,000 lakes in Tamil Nadu. Now, almost 50 per cent of the lakes have been encroached upon in the name of development. Local bodies, farmers and stakeholders should take up the cause of maintenance of lakes.”

He is an apex body member of Siruthuli, and works closely with INTACH, RAAC, KARAM (Kovai Aid for Rehabilitation and Motivation, set up during the Tsunami), and is the joint secretary of Nannari Kazhagam that visits educational institutions and speaks to students on culture, values, environment, history and nature.

Every single stone speaks volumes on history, says Jayaraman and quotes a line from a Perur templekalvettu .

“‘Devisirai anai adaithu, kolur anaikku sedham varadha padikku,” (while constructing a dam, it is the people living downstream who should be first taken care of). If we follow that thought today, we have a ready solution for the Cauvery water dispute,” he smiles.

Noyyal is a small but significant river. It starts off its 167-km journey from Kooduthurai near Alandurai and joins the Cauvery near Karur. Jayaraman records the details in books such as Noyyal Nijangal, Noyyal Thayum Siruthuli Seyum and INTACH’s Kongunaadu Patrika. Jayaram describes Coimbatore as a beautiful woman adorned with a garland of Navaratnams represented by the lakes at Narasimhapathy, Krishnampathy, Selvampathy, Puttuvikki, Selvachintamani kulam, Puliakulam (now a town), Vaalankulam, Kurichikulam…

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus> Society / by K. Jeshi / Coimbatore – January 30th, 2014