It’s the holy hill, the miniature mount of miracles, the anchor you rely on when adrift in foggy doubt. Close to two thousand years ago an apostle was martyred on its summit, his gore reddening the soil. On the western outskirts of the city of Chennai (formerly Madras) on the southeastern coast of India, the hill called St. Thomas’ Mount juts up 300 feet above the sea level. The city’s airport lies just beyond the hill and, depending on the time of day and the flight path, one can get an aerial glimpse of the hill from within an aircraft landing or taking off, just as one can watch planes land and take off from atop the hill. But the hill looks so ordinary, so nondescript, that passers-by on the ground or travelers in the air scarcely give it a glance.

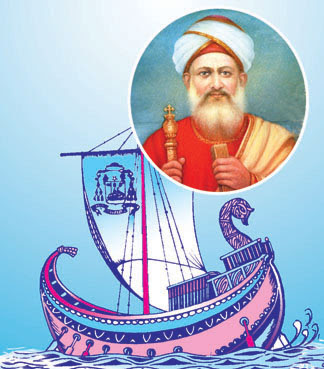

Converting from one faith to another is not such a facile exercise as is thought. While you might harbour the conviction that the new faith is propelling you towards salvation, can you so easily let go of old customs and relics that comforted you so often and so much down the years? And so the Nasrani designed their cross after the Jewish menorah, the stand of seven candlesticks.

In the Jewish tradition, the central candle is the main candle from which all the others branches are lit. (Interestingly, the Hebrew word for branch is Netzer, the root word for Nazareth and Nazarene – and therefore, also for Nasrani.) The Nasranis converted the middle candlestick of the menorah into an ornate cross, with three candlesticks (or images representing three candlesticks) flanking the cross on either side. These six branches represent God in the form of the burning bush. Flying vertically downward towards the cross is a dove, its beak touching the top of the cross; this represents the Holy Spirit. This menorah-cross is known as the Nasrani Menorah. It is also referred to as the Syrian Kurishu (the Syrian Cross).

The menorah is not the only aspect of Jewish tradition that the Nasrani Syrian Christians have retained. Another tradition that lives on is the partaking of the Pesaha-Appam, or unleavened Passover bread, along with Pesaha-Paalu, or Passover Coconut Milk, often flavored with unrefined brown sugar, ginger, cumin and cardamom. The Nasrani church has separate seating for men and women, and the sanctuary is partitioned off by a thick red drape until about the middle of the Qurbana (the Nasrani Mass). Until the 1970s, the Qurbana was recited in Syriac-Aramaic; the Nasrani baptism is still called by its Syriac name, Mamodisa, and follows many of the original rituals associate with this rite of passage. The Birkat Hamazon is recited after the blessing of the Holy Eucharist, and as a Thanksgiving blessing. Marriages invariably take place within the community.

As noted previously, in Malayalam (the language of Malabar/Kerala), Thomas of Cana became Knai Thomman. Could this community bearing the Thomas name, then, have got mixed up with the Apostle Thomas? The distinctive Nasrani menorah crosses, carved by the early Syrian Christians in Kerala, may have been attributed to the Apostle Thomas, since it is quite possible to get confused with two names that are similar. That would explain how the Nasrani Menorah in the church on St. Thomas Mount, the cross that sweated blood, got linked to St. Thomas though it is unclear how it travelled coast to coast, from Kerala on the southwestern coast to St. Thomas’ Mount on the southeastern.

Could St. Thomas have carved it? The Nasrani menorah is very distinctive; it came to southern India only around 345 AD, whereas St. Thomas was said to be there three centuries earlier, between the years 52 and 68 (or 72) AD. Also, if St. Thomas had carved a symbol during that time, would it have been a cross at all? Scholars say that the cross did not become a symbol of Christianity until sometime in the late second century AD. The cross was a very visible reminder of deliberate torture, suffering and death — a hated and grisly method of public execution, besides being irrevocably associated with the death of beloved Jesus the Christ, the founder of their religion. The early Christians used, not the cross but the Ichthys (Fish Symbol) to represent their faith. Did the Apostle St. Thomas even visit the hill that bears his name?

If stones could speak, we could whisper to each of the Nasrani menorahs scattered across Kerala, and to the Bleeding Cross, and they would whisper their stories back to us, tales of hope and fear, of bravery and cowardice, of longing and satisfaction. But as that is not possible, we must wait for historians and scholars to probe back in time to determine the facts, decipher them and solve these puzzles from the past.

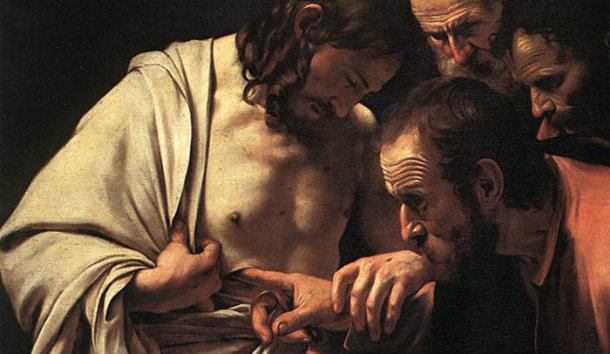

Historians and scholars, however, do not always agree with each other both on the authenticity of discoveries or their interpretation. After his martyrdom atop St. Thomas Mount, the remains of the apostle were taken to Edessa in Mesapotamia (modern-day Urfa in Turkey) and interred there. But there is a relic in the church on St. Thomas Mount, a finger bone, purportedly the one that probed the wounds of Christ. Along the way to Edessa, relic seekers seemed to have helped themselves to many of his other bones as well. Roman Catholic records say the Apostle was buried at Ortona in the Abruzzi region of Italy; the Greek Orthodox claim that Thomas’s skull rests on the island of Patmos in the Aegean, but leaves us unclear about where the rest of his body is, and when and why the two were separated. As one commentator put it tongue-in-cheek, if all the bony relics of the apostle that are on display in various churches and museums were collected and assembled, we would end up with one and a half skeletons.

Christians in India take pride that their religious heritage can be traced to a direct disciple of Christ. Pope Benedict XVI caused a lot of angst and heartburn among many Indian Christians when, during his September 27, 2006 speech at the Vatican, he mentioned that St. Thomas evangelized Syria and Persia and then went on to Western India, from where Christianity spread to other parts of India, including the South. In other words, the pontiff seemed to be dismissing the legend that the Apostle Thomas was ever in South India. After the cries of outrage from the Indian Christians, the Vatican took the unusual step of amending the published text of the pope’s speech.

But such doubts have been raised before, even by those in the church hierarchy. In 1729 the Bishop of Madras-Mylapore wrote to the Sacred Congregation of Rites in Rome for clarification about whether the tomb in the San Thome Cathedral of Madras was indeed that of St. Thomas. Rome’s reply was not published. A century later, in 1871 the Roman Catholic authorities at Madras were “strong in disparagement of the special sanctity of the localities [San Thome Cathedral, Little Mount, and St. Thomas Mount, the three areas in Madras associated with St. Thomas Mount] and the whole story connecting St. Thomas with Mailapur.” But in 1886 Pope Leo XIII stated in an apostolic letter that St. Thomas “travelled to Ethiopia, Persia, Hyrcania and finally to the Peninsula beyond the Indus”, and in 1923 Pope Pius XI quoted Pope Leo’s letter and identified St. Thomas with “India”. However, historians note that many ancient writers loosely used the term “India” to refer to several territories east and south of the Roman Empire – including Abyssinia, Mesopotamia, Parthia (Persia/Iran), Arachosia and Gandhara (modern Afghanistan/Pakistan), and parts of Arabia, especially the coastal territories (modern Yemen and Oman).

Historians have neither conclusively proved nor disproved that St. Thomas was ever in southern India. And the stones will not speak.

Each individual experiences two types of hunger, the material and the spiritual, in varying degrees of proportion. The most common pang of spiritual hunger is groping for answers to the eternal questions: Who am I? What am I doing here?

We are born with material and spiritual components, the gross and the ethereal. The material is easy to relate to, but the spiritual is more nebulous. Some see spiritual matters as concerned with our ultimate nature and meaning, not just as biological organisms but as beings with a unique relationship with the spirit that transcends time, space and the material sphere. Others view spirituality as the nurturing and development of one’s inner life.

In a great many minds, the institutionalization of religion is now associated bloodshed, division, incredible cruelty to other people in the name of evangelism or jihad or some other form of crusade, forcible religious conversions, and so on. It also brings images of being punished for sins or erroneous ways, many of which are all too human.

Religion aims to rise and soar above the worldly plane yet organized religions have been continuously seduced by a material focus. Atop St. Thomas Mount, you need permission to photograph the church interiors and the relics, and the granting of the permission is accompanied by a request for a donation. The staff member in charge tries to gauge where you live to suggest a donation amount. Donors are offered a book to sign in (and record the donated amount), and a glance shows that visitors from overseas have donated far larger sums than the locals.

There are two large Hindu temples north and south of St. Thomas Mount: the temple of Lord Venkateswara in Tirupati, and the temple to the Goddess Meenakshi in Madurai. The Tirupati temple is the wealthiest Hindu temple, and reputedly the richest and most visited religious shrine in the world. The Madurai Meenakshi temple is an ancient temple, famed for its stunning architectural complexity. Many such temples that draw crowds of devotees have complex queue systems to make you line up just to flit past the sanctum sanctorum and get a momentary glimpse of the deity.

But Mammon can insinuate his way anywhere, even in houses of worship. So in many temples there is more than one line. There is a line where there is no charge, and there is a line where you need to purchase a ticket. Since the first line is hopelessly long, people purchase tickets. They still have to wait, but for a somewhat shorter time. Then there are the super high-priced tickets that permit you to jump both lines and sneak up first.

Now, material houses of worship do need material means for their maintenance; this is why an offertory basket is passed around at church services. And when there are throngs of hundreds and thousands of pilgrims, there needs to be some sort of regulatory system to maintain order. But the whole notion that paying more money ushers you into the divine presence ahead of those who paid less has something repugnant about it. After all the idol is not God, it is merely an image to remind you of God or of certain aspects of God. For example, some Hindu deities are depicted with multiple heads (God is omniscient) or multiple hands (God is omnipotent). An omniscient, omnipotent God is everywhere, not just restricted to the sanctum sanctorum of the temples, or on the altars of churches or synagogues. If stones could speak, this is what the idols of the deities would say, adding that those that understand this and feel the presence of the divine all the time have no need to lighten their wallets or purses to stand in line for a long time to get a glimpse of an image.

In organized religion more attention is paid to the external aspects of religion (the appropriate vestment for priest and bishop, the proper items for a puja ceremony), and to the hierarchy within a religion, or to the rules that govern that particular faith, than to the inner experience of religion itself. A great many cling to the outer trappings. As described earlier, the Knanaya Christians have retained their Jewish traditions to the point they are sometimes even referred to as the Jewish Christians, a term that can raise both eyebrows and hackles in other parts of the world. The throngs at St. Thomas’ Mount firmly believe that the cross will bleed once more, and attribute all kinds of explanations (including the effect of their collective sins, their karma en masse) for why the flow of blood has been stanched for three centuries. Hindus who have been proselytized to Christianity bring their caste baggage with them; once Hindu Nadars and Pillais, now they are Nadar Christians and Pillai Christians, and the old eddies and undercurrents still flow strong though all of them are supposedly One in Christ.

But times have changed and are changing. Whether it is due to the advancement of science and technology and the new ways of thinking that this brings, or whether due to other factors, the wholesale reliance on belief is eroding. In bygone times, belief was the cornerstone of religion. Today, the numbers of people who place emphasis on individual spiritual experience rather than belief is growing. “I’m not religious, but I’m spiritual” — how often have you heard that phrase?

And yet, often it is their religion that has helped to unfold their latent spirituality, and still has repositories of wisdom nuggets buried within its voluminous folds, though sometimes a spirited excavation is required to find them.

If stones could speak, could they tell us the whole story of the two Thomases — the apostle Thomas and the Nasrani Thomas? As the stones at one church may say, “We’ve been resting on this very spot for centuries, and we can tell you what went on here, but you’ll have to travel to other parts of the country and talk to the stones there, and then piece all the information together.”

“All right,” you respond, but the stones then gently remind you that the other stones who might have been witness to significant events may no longer be there, either carted away to other unknown destinations, or simply blown into smithereens by dynamite and bulldozers clearing the land for new development. So many stones, blown up into enough silicon dust to fill up a valley, indeed, many valleys, taking with them all their collective memories.

“But why,” one of the older, wiser stones may ask, “do you want to know this? What real difference will it make? If you can trace your faith lineage down the byzantine alleyways of history to St. Thomas and directly to Christ, does that put you a cut above your fellow Christians who cannot claim such a pedigree? Which religion do you follow — the religion of Jesus the Christ or the religion built around Jesus the Christ?”

People extract meaning from symbols and imagery of religious tradition. In the beginning, this may be useful in helping to focus the distracted mind on the idea the symbol represents. But this is the means, not the end. The ninth-century Chinese Buddhist master Linji Yixuan said, “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him ….. Then for the first time you will gain emancipation, will not be entangled with things, pass freely anywhere you wish to go.” One can replace Buddha in the quote with Christ or Moses or any other religious figure. What is implied here is that when you convert a spiritual leader into a sacred fetish that then becomes larger than life, you miss the core essence of his teachings. And the greatest tribute you can give your spiritual preceptor is to follow his teachings. How many actually do that?

If stones could speak, perhaps one of the wise among them would say, “Don’t hang around here waiting for stone crosses to sweat, or to gawk at pieces of bone and faded paintings. Go back to your daily routine, but reach out to other people. Forgive them if their faults have roiled you, bless them, see the innocence in them, give them a real loving hug. Those are the kinds of things it all boils down to.”

And another stone might add, “We have learnt much by sitting still in the silence. And so should you. Walk barefoot on the dew-bedecked grass in the early morning, and feel it caress the soles of your feet. Enjoy the sunlight filtering through the leafy trees, and the clouds rolling across the bright blue sky. Gaze at the stars at night, pierce through space and permit yourself to soar heavenwards until you are one with them.”

source: http://www.praguerevue.com / The Prague Revue / Home> In the Stream by Vishwas R. Gaitonde / January 01st, 2014