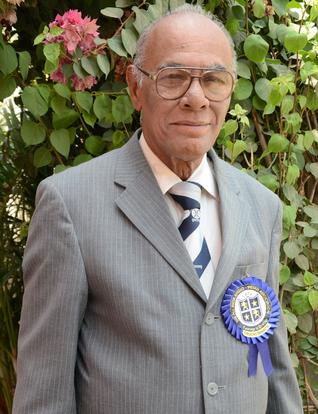

George Evers has been the anchor at hundreds of Anglo-Indian weddings and social events since the 1960s. He tells Nahla Nainar how he became an accidental emcee

No Anglo-Indian wedding or social gathering in Tiruchi has been complete without George Evers as the master of ceremonies. Despite emceeing nearly 900 weddings however, Mr. Evers is hesitant to call it a profession.

“Emceeing came accidentally into my life,” says Mr. Evers, 77, as his dog Molly and wife Doreen give him company at their home in Karumandapam. The then-Southern Railways clerk was asked to take over as master of ceremonies from a colleague who had emigrated to England in 1962, and since then, has been “stuck into it,” till as recently as 2014’s New Year party.

“Even now, when I say I’ve gone too old, people want me to host their functions. I have emceed functions of several generations of families, mainly as a friendly gesture. I can’t call it a profession as such, because I didn’t really earn money from it. After I stopped working in 1995, people began to think that ‘Uncle has retired, maybe he requires some money,’ and they’d pay me something. But all along, I’ve never quoted any rate for my work,” says Mr. Evers.

In his heyday, Mr. Evers also remembers being the master of ceremonies at a function in Thiruvayaru, considered the birthplace of Carnatic music. “My main advantage was that I could sing with the orchestra. Whenever the band boys would run out of songs, for the Railway Institute’s ballroom dances for instance, I’d take the microphone and belt out a few numbers to keep the patrons happy,” he says.

Busy calendar

Working in the Railways let him keep up his alternative job as his rail-pass helped out in the commuting. “Sometimes, I used to be sent conveyance, but mostly I’d just hop on and off the trains – I’ve been to functions in Madurai, Erode, Villipuram, Nagapattinam and so many other places. I made a lot of friends during these occasions. I really enjoyed what I did, and of course, it was because my wife was very co-operative. Doreen sacrificed a lot to just let me do this.”

Such was his popularity that Mr. Evers was persuaded to return as an emcee after a stroke in 2004 paralysed the left side of his body for over a year. “I don’t think I’ll be up to it this year, because my eyesight has weakened,” he rues.

Nostalgia

Mr. Evers grows nostalgic when he speaks of his childhood, as the ninth born of a family of five boys and five girls. “My father Isaac Martin Evers was a railway guard. He had no knowledge of his parents, but my Dad did tell me he studied in Adyar (Chennai) at St. Patrick’s convent school. My mother’s father was Irish,” says Mr. Evers.

The young George Evers started kindergarten at the Madurai Railway School, and then, when his father retired in 1944, the clan shifted to Mannarpuram, Tiruchi. “Since 1944, I had my schooling in Campion (Anglo-Indian Higher Secondary School) and finished Matriculation in 1954,” he says. “I joined the Railways in 1957 as a commercial clerk, with my first posting at Dhanushkodi.”

Mr. Evers shifted back to Tiruchi after marriage to Doreen, his neighbour in Mannarpuram, in 1962 and has stayed on here since then.

The memories that the couple share of Tiruchi hearken back to a time when there were few automobiles on the roads. “Most of the children used to walk to school, Campion for the boys and St. Joseph’s convent for the girls,” says Mr. Evers. “Some boys used to even walk all the way from Golden Rock (Ponmalai) if they had missed the 8.30 a.m. Students’ Special train. It was good, kept us healthy. Besides, there were no buses or cars crowding the roads then. Motorbikes were still rare, and owning a bicycle was a luxury,” he adds.

“My parents put us boys in boarding at Campion because they felt it would make us independent and disciplined,” says Mr. Evers.

At home, the lifestyle had an Indian flavour with a Western finish. “We’d have dosai and chutney for breakfast, but bread, butter and jam was always there on the table,” recalls Mr. Evers.

“Our Western culture and our fluency in English helped Anglo-Indians secure jobs in the Railways, Customs and Telephone departments,” says Mr. Evers. “But as the years go by, I feel our community has become more Indian. After all, if you are going to live in Tamil Nadu, you’ve got be a Tamilian, you can’t live like a Britisher.”

As in the case of many Anglo-Indian families, inter-racial marriages have become common. “Even within my own family, my daughters-in-law are Tamilian,” says Mr. Evers. “We don’t have the custom of arranging marriages in our community. In my case, my mother and father had nothing to do with our marriage. I had seen Doreen and fallen in love with her and we had to get permission from her parents to get married. Our parents just set the date,” says Mr. Evers with a twinkle in his eye.

The days ahead

The abolition of job quotas for the Anglo-Indians in the 1960s led to an exodus that continues today. “In Tiruchi, I think around 3000-4000 families have stayed on, though many people left for United Kingdom and Australia in the 1970s and ’80s,” says Mr. Evers, who is a member of both the Campion Old Boys Association, Melbourne and All India Anglo Indian Association.

“We never used to get huge salaries like today,” says Mr. Evers, adding that he was earning Rs. 2500 when he retired. “But we were able to keep the wolf from the door, because the commodities were not so costly then.”

The Evers have six children (five sons of whom the eldest passed away in 2001 and a daughter), and six grandchildren. So would Mr. Evers be doing the honours as emcee at his grandchildren’s weddings?

“If God spares us,” laughs Mrs. Doreen as her husband smiles at the suggestion.

Dancing the nights away

Mr. George Evers on how dance has defined Anglo-Indian social life in Tiruchi

“The Railway Institute the Head Post Office was converted by Europeans into a dance hall. They used to have regular dances there, with live band on stage.

“To know how to dance became part of the culture. And if you didn’t know how to dance, there was no point in going to the Railway Institute, because you’d just have to sit down.

“There used to be many styles of dancing – slow fox trot, fox trot, waltz, rock and roll – all that used to be called ballroom dancing.

“People don’t patronise Western dance now like they used to, even during the festive season. Another main reason is that the children have to go back to school on January 2, which makes it tough for parents who want to dance away the night on New Year’s Day. They can’t stay up late and then rush to get the children ready for school the next day.

“This New Year’s ball was very disappointing. In 1967, there used to be no less than 800 people in the hall, and there would be at least 300-400 couples on the floor, dancing. But on the first of this year, there were only four-five couples on the floor.

“In those days they’d dance till six in the morning, and even when I’d tell them to go home, they’ll plead ‘one more song’, ‘one more song’. So I came up with a solution: I’d tell the band boys to play the national anthem!

“Everybody would stand to attention, and couldn’t ask for more. That became my signature closing tradition.”

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus> Society / by Nahla Nainar / Tiruchirapalli – April 05th, 2014