The English championship is two months away and fans are making plans to be there. But the first family of Indian tennis has other ideas

No sprightly girls and boys to chase the yellow balls. No linesmen to yell out calls. No electronic board to flash the scores. But superlative matches are played every day at this grass court, where tall trees fill in for spectators.

These ‘matches’ defy the humdrum order of time, space and sequence. One moment, an iceberg-cool Borg and a fiery McEnroe are locked in a nail-biting tie-breaker. In the next, Ashe gets the better of Connors with a clever mix of slice and spin. Then come Nadal and Federer fighting a war of attrition, which is followed by an emotion-soaked final where a kind Duchess of Kent offers her shoulder to a teary-eyed Jana Novotna, disconsolate after her loss to Steffi Graf.

Welcome to the private grass court at Oliver Road in Mylapore, maintained by Indian tennis’ first family, the Krishnans, as a tribute to Wimbledon. For the Krishnans, this natural grass court, which borrows features from the hallowed courts of Wimbledon, serves as a mind screen to replay and relive the timeless matches from the prestigious English championship. (Also significant is that this court is one of the very few natural grass courts in the country.)

“Wimbledon is dear to every member of our family. We have followed the championship closely for decades,” says Ramanathan Krishnan, 77 now.

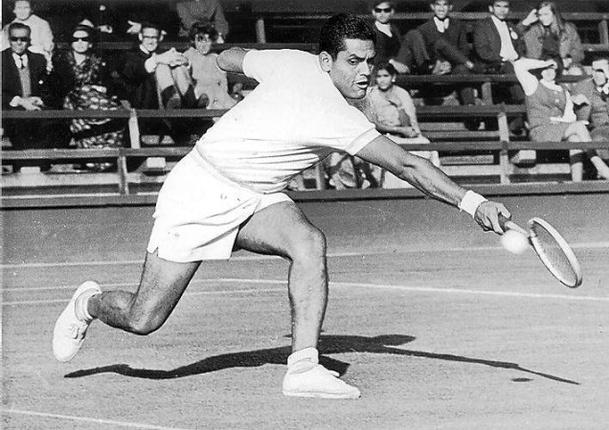

The Krishnans not only tracked Wimbledon, they also excelled in it — a fact that largely shaped their deep attachment to the championship and also the decision to design a natural grass court patterned on those at Wimbledon. Ramanathan Krishnan is a two-time semi-finalist (1960 and 1961) at Wimbledon and his son Ramesh Krishnan, the winner of the 1979 Wimbledon juniors title and a quarter-finalist in the men’s section in 1986.

“It was our son Ramesh’s idea to design a Wimbledon-type grass court at our house on Oliver Road. Around four years ago, he came up with this plan and everyone was excited about it. Ramesh got all the necessary information from Wimbledon. My wife Lalitha assisted in executing the project. And when it was done, we knew we had brought Wimbledon home,” declares Ramanathan, who spends the evening hours with Lalitha at this private grass court, both of them merrily parked in broad, deliciously comfortable bamboo chairs. “When Wimbledon is on, we bring out the television set and watch the matches sitting here,” says Lalitha, 70.

The Krishnans are going to a lot of trouble to make Wimbledon more immediate for themselves: they have put two men, A. Shanmugam and M. Manickam, on the job of maintaining the court. Natural grass court maintenance is costly and cumbersome, the reason we don’t have many of them around.

Notably, this grass court is not used regularly — for ‘real’ matches, that is. “Once in two months, Ramesh, who lives in R.A. Puram, brings some of his friends along for a game,” says Ramanathan.

Besides the love of Wimbledon, there are other sentiments that spur the desire to keep the court in shape and working order. Beneath the grass, lie clayey memories of long practice hours and family bonding. “This was a clay court for well over three decades, before it was turned into a grass court four years ago. We set up the clay court in 1975. It was a training ground for Ramesh,” says Ramanathan.

“Father would train Ramesh from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. at this court,” recalls Gowri Krishnan-Tirumurti, Ramanathan’s daughter, who also trained at the court and is the 1982 Indian national juniors champion.

In its clayey days, the court saw five south Indian champions play and practise the sport — T.K. Ramanathan, Ramanathan Krishnan, Ramesh Krishnan, Gowri Krishnan and Shankar Krishnan (a cousin of Ramesh and Gowri). “Just like my dad and brother, Shankar went on to play Davis Cup,” says Gowri.

This private tennis court may have created champions, but its charm lies in the sense of togetherness it has fostered among the Krishnans. “I remember when we would be practising, our mother would sit on the sidelines and peel oranges for us,” says Gowri.

The bonding has extended to the youngest generation. Ramanathan’s grandchildren — Gayathri, Nandita, Bhavani and Vishwajit — are in their twenties and studies have taken some of them away from home; yet, when they visit their grandparents, they love to sit around this clay-turned-grass court. Says Gowri, “Successive generations have learnt many things around this court. Discipline is one of them.”

And, surely, also what it takes to be a winner.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus> Society / by Prince Frederick / Chennai – April 25th, 2014