Study of homes

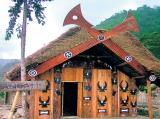

She has pored over curvilinear walled houses in Upper Volta; shell-decorated chieftain’s houses in the villages of Fijian Islands; dome-shaped huts with stilt legs in Samoa Islands, Polynesia; huts with pitched roofs and a front porch in fortified Maori villages (New Zealand); castle-style farmhouses in the Taiaakon region (Dahomey); the large togunas (public buildings) supported by carved pillars in Mali; the diverse structures of Morocco; dwellings in British Columbia with free-standing totem poles in front of them; the log huts of Lapps in Scandinavia, and the huts of Naga Angamis.

There is more: the cusped roof structures with horns as insignia of rank in interior Assam; huts with saddleback roofs in New Guinea; dwellings with geometrically decorated walls in Mangbettu (Zaire); temporary shelters made from branches and pandanus leaves in Solomon Islands, Melanesia; keel-shaped tents of Ethiopian nomads; huts covered by mats and bent branches in eastern Madagascar, aboriginal cave dwellings in Australia…

And yes, she has been to Timbuktu!

Well, for Chennai-based Rohini Shanker, the study of primitive architecture around the globe has been a relentless, fascinating and satisfying three-decade odyssey. The charm never seems to wear off.

It sparked off when she first set foot in interior Alaska. Conical tents greeted her. “It was a shock. I had seen the same kind of structures in Mongolia on the other side of the globe,” reminisces the architect and designer. For Rohini, this exploration grew as a casual offshoot of her frequent travels abroad to attend conferences. She began to take a day or two to travel beyond the tourist spots. “It’s beautiful that tribal people see the entire land as their abode, their architecture. They are gentle and sociable, there is nothing aggressive about them. If they are afraid of you, they will keep away from you,” shares Rohini.

Giving it a skip

Strange as it seems, primitive architecture is a realm that has been overlooked by everyone — archaeologists, historians, and even art enthusiasts. Most architecture pundits tend to give primitive architecture short shrift, considering it to be a temporary solution to an existential challenge, and a dead end that really didn’t evolve into much. But that may not be the case, as pointed out by the architectural theorist Marc-Antoine Laugier.

Recall that as early as in 1755, Laugier had elucidated in his seminal but overlooked essay, Essay on Architecture, that the aesthetics and architecture of ancient Greek temples were drawn from the plan of the primitive hut, which is considered the oldest of habitations built by man. As he pointed out, the basic Doric style of architecture was inspired by the hut’s format in which a horizontal beam was supported by vertical tree trunks embedded into the ground, with a sloping roof to channel rainwater into the ground.

Considering the range of architectural features that come alive in the ancient primitive dwellings that Rohini Shanker has documented, it would be interesting if someone were to study them in depth.

While some of the features are quite apparent, others don’t hit the eye straightaway, and some other similarities are downright puzzling.

For instance, the pagodas of Buddhist temples bear something in common with the saddlebacked roofs in New Guinea, though the geographical and cultural distance between the sites dissuade the speculation. Likewise, the dome-shaped huts of the Polynesian islands show a definite resemblance to the domes of Islamic architecture. Nevertheless, leaving aside the road taken by primitive architecture, some of these structures are marvels by themselves.

Consider the case of the primitive tribes who live in Andaman Islands. “With just poles and leaves they build such simple and sturdy structures that bear the brunt of the sun, wind and of course, the islands’ spectacular and notorious monsoons. They manage this miracle because the structure is built in a way that allows the wind to blow through it rather than blow on it. I saw similar structures in Congo, but the foliage used for the roofing was different,” recalls Rohini.

Of course, primitive architecture cannot be viewed in isolation. Like other aspects of art and culture, it reflects a certain attitude towards life. Chiefly, a reverent and non-disruptive attitude towards nature. This is something that gets confirmed over and over again with any and every primitive dwelling that you consider.

Let live

Rohini points out to the aboriginal settlements in Uluru in Australia, which is an annual visit that she hasn’t missed for the last 30 years. “Without gadgets they know exactly where to find food and water, the raw materials to build their shelter, the mineral-rock pigments to make their dot-paintings, and the reeds to make their musical instruments (like didgeridoo). Their culture and attitude towards our planet is wonderful. Though this land is so tough to live in, they leave no footprint of themselves there. Not for building their homes, not for meeting their other needs,” remarks Rohini.

This is one of the reasons she reckons that we shouldn’t rush to ‘civilise’ the tribes who live in their own ‘archaic’ ways. “They continue to lead a happy life, without our lifestyle diseases. We shouldn’t enforce their culture, unless they ask for it,” is Rohini’s explanation.

The needs of primitive people by way of habitable structures were limited — a hut for home, a shrine for worship, a granary for storage, a stockade for defence, a cairn/mound as a grave marker of the shaman, chieftain and priest. But within the limitations of their needs, as also the limitations of the resources and the technology they have at hand, primitive architecture holds some elegant and fundamental solutions for architectural challenges, which is something that modern architects might ponder upon.

“I once asked a little child to draw houses, and I was amazed to see her come back with just rectangles. The child has seen nothing but our cuboidal blocks, towers and tenements. Well, that is the state of our architecture today, with most urban buildings tending to be just blocks. In this context, nobody realises just how exciting, interesting and rewarding studying primitive architecture can be,” remarks the architect.

source: http://www.deccanherald.com / Deccan Herald / Home> Supplements> Sunday Herald / by Hema Vijay, DHNS / June 14th, 2015