Saving the MLS treasures

It was one of the happiest mornings I’ve spent in a long time when I recently went to the Madras Literary Society which was holding a minuscule exhibition to celebrate World Heritage Day. Two things made the morning special. First to see a group of YOUNG persons, led by Rajith Nair, a heritage walks leader, and two architects just getting into their stride, Tirupurasundari and Sivagami, not only enthusiastic about heritage but also wanting to breathe new life into what still feels like a mausoleum, the MLS. The second thing was finding that the MLS still has a few treasures by way of old books, even though more than half its collection had vanished at the time I had first visited it in the early 1970s.

The exhibition, tiny as it was, had me pausing at exhibits longer than at most other exhibitions. There was a frieze of old advertisements that had me stopping because they looked so familiar and out of my youth. W.M.A Wahid, one of them, was where I had bought all my school textbooks and notebooks. And then Sivagami produced their source — and that again took me back to beginnings. This was The Times of Ceylon One Rupee Diary that her grandfather had used when he was in Colombo in the 1950s. Then there was Tirpurasundari showing me an old inkwell-stand-cum-pen-holder-tray. “It had belonged to my grandfather’s grandfather,” she said. And much of the other exhibits the two young architects had put together had rather similar histories.

The two architects, virtually self-taught on paper conservation, are also leading a ‘Restore a Book’ project, whereby old books are being restored in scientific fashion with support for each such book coming from a donor. Both donors and volunteers are needed — and I couldn’t help wondering why, with Women’s Christian College next door, a team of dedicated volunteers couldn’t be found there. If we get enough volunteers, we’ll be able to save all the valuable old books in the library in a year, working every Saturday, says an enthusiastic Tirupurasundari.

One of the 14 old books saved till now is a 1798 edition of Captain James Cook’s Voyage in the Pacific Ocean. But interesting me even more was a tabloid-size book of Tripe’s photographs of Madurai that was awaiting restoration.

I was positively over the moon when I was told there were 11 more such volumes, of Trichy, Thanjavur etc. Tripe had been commissioned by the Government of Madras to record all the historic structures in these areas and he did so in 1854-1860. And then just as I was leaving I spotted Forest Conservator Ganesan poring over a book that kept me for another hour at the MLS.

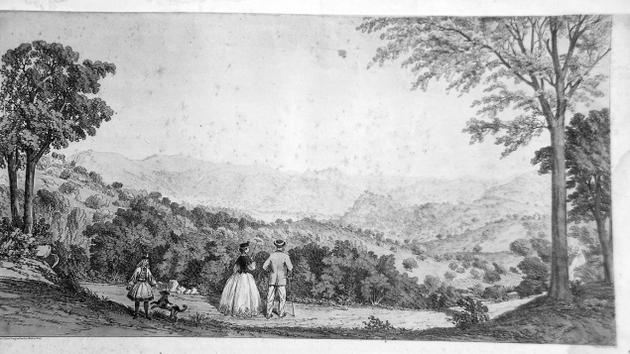

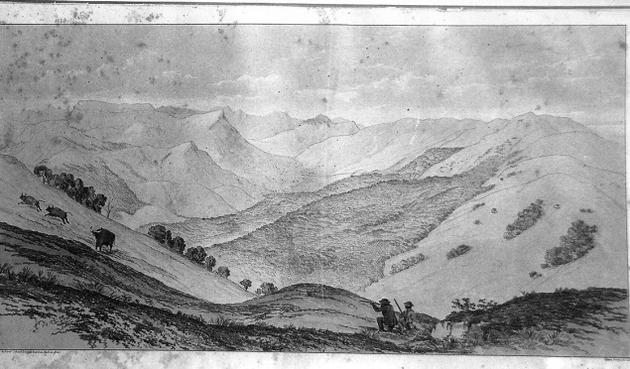

The book, again the size of the Tripe volumes, was of Capt Douglas Hamilton’s sketches of Yercaud and the ‘Pulni’ Hills.

He too had been commissioned by the Government to record the hill stations of what is today Tamil Nadu and what he did was some wonderful pen and ink sketches — eight of them of Yercaud, which revived memories of the year I spent in school there. Tripe’s pictures, Hamilton’s sketches and perhaps any other such pictorial material deserve an exhibition of their own — if only there was a sponsor.

Meanwhile, Tirupurasundari and Sivagami and their small team are looking for volunteers for their restoration project as well as to help with a second project: the reorganisation and classification of the entire collection. Contact them at tsarchi2007@gmail.com or rajith.bala@gmail.com

For the record, the Madras Literary Society is the oldest surviving library in India, its beginnings dating to 1812.

***

A Seven Pagodas’ neighbour

When my Australian correspondent Dr A. Raman finishes with papers he has used for research for the numerous articles he writes for a variety of publications every year, he sends them to me to forward to the Roja Muthiah Research Library. And usually amongst them are a couple of papers that grab my interest. Last week’s consignment had one paper that fascinated me: Descriptive and Historical Papers Relating to The Seven Pagodas of the Coromandel Coast. Edited by Capt. M W Carr and published in 1869, it included eight articles by British scholars who had explored and researched Mahabalipuram. Their findings were fascinating to say the least.

The Editor’s note began with these words: “The papers contained in this volume… have been reprinted in a collected form, under the order of the Government of Madras, with a view to promote the intelligent study and examination of these interesting relics of a bygone age.” I wonder which Government in India today, State or Central, will think in such terms.

Be that as it may, Carr writes, summarising the papers, “The origin of the European Appellation cannot be satisfactorily traced… (but) as stated by Dr Graul’s guide it may refer to the five Rathas, the Ganesa temple and the Shiva temple. The story of magnificent pagodas swallowed up by the sea is apocryphal…” Carr goes on, “A matter of greater importance, the age of the Sculptures and Inscriptions… has not …been definitely ascertained.”

Carr points out that Fergusson had thought the rathas had been carved in 1300 CE and were an architectural transition from Buddhist to Hindu styles. Walter Elliot dates the Tamil inscriptions to the latter part of the 11th Century and the Sanskrit ones “not later than the 6th Century”.

No doubt there are a heap of latter day views, but it does seem that the sculptures and inscriptions do not have definitive dates. Shouldn’t we be searching for them?

While this is an old debate, new to me was mention of a place called Saluvan Kuppam, about two and a half miles north of Mahabalipuram. Here there are several rocks that have been sculpted, there is amandapam/temple with a lingam, and several inscriptions. A frieze above the temple entrance bears in Old Tamil the word ‘Atiranachandapallava.’ Do these remains still exist or has the sand swallowed them? If they do, shouldn’t there be some focus on them for any visitor to Mahabalipuram, no matter how insignificant they seem. Like Tiger’s Cave, they would certainly indicate extent of settlement.

Elliot, examining the inscriptions in and around Saluvan Kuppam, goes into a long discussion about them that is beyond me. But I note two points that he makes at the end of it all:

1. “In a copy of a grant at Pithapur, in my possession, Vijayaditya, the founder of the Chalukhya dynasty of Kalinga, about the middle of the 6th Century, is described as destroying the southern King Trilochana Pallava… (who) it may be inferred… was of the same race and probably the same family as… Atiranachanda Pallava.”

2. “From these facts it may be inferred that the rulers of Mamallapura were in a state of independence in the 6th and beginning of the 7th Centuries. We know from other sources that the Chola kings reduced Tondamandalam about the 7th Century.”

None of this makes the history and implication of the inscriptions in and around Mamallapuram indisputable. But what I want to emphasise is that much study was going on in the 19th Century to understand and unearth the secrets of Mahabalipuram. Is the same effort going on today?

***

Malabars and Malabar

R Seshadri, quoting Wikipedia, tells me that “Malabars is an appellation originating from the colonial era that was used by Westerners to refer to all the people of South India (Tamils, Telugus, Malayalees and Kannadigas included)” and not confined to Tamils (Miscellany, April 11). I’m afraid I don’t quite agree with him. Wikipedia, I have found, is not always the last word on a subject.

In this case, Malabar was first used by the Portuguese to refer to the people of what is now Kerala and Tamil Nadu from the time they landed in Calicut in what was Malabar.

The first type for printing in an Indian language was cut in Tamil script and the language of their publications in the 16th Century using this type, the first was in 1578, was called Malabar. Kannada and Telugu came nowhere in the picture at the time.

As far as I know, Old Kannada script (10th-18th Century CE) derived from Kadamba Script (5th-10th Century CE) which in turn derives from Brahmi script. Telugu script deried from Old Kannada script, the separation beginning in the 13th Century and finalising in the 18th Century.

I’m no expert on the subject, but perhaps someone would like to add to this and point to any links the two languages have with Tamil (Malabar).

The Telugus, mainly on the east coast of India, were referred to by the early European settlers as Gentoos. It was well into the 18th Century before the Europeans moved into what is now Karnataka and caught up with the Kannadigas. The only Karnataka contact they had before that was along the Konkan Coast and the Portuguese recognised them as Konkanis.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus / by S. Muthaiah / Chennai – April 23rd, 2016