/ The Hindu

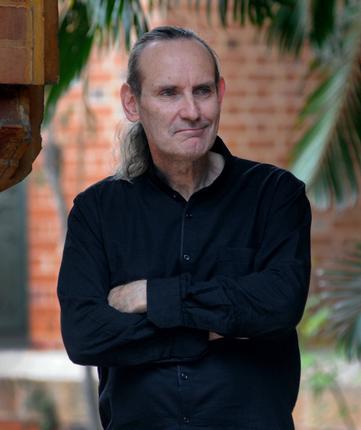

Denmark’s Mikael Stamm in his search for philosophical answers ended up doing his Ph.D in Saiva Siddhanta at the University of Madras.

Philosopher Hume wrote that books on metaphysics contained nothing but “sophistry and illusion.” Most analytic philosophers were inspired by Hume’s condemnation of metaphysics. The logical positivists even tried to develop artificial languages, which, by their very nature, would make it impossible for metaphysical questions to be asked in those languages. The Vienna circle, which not only included philosophers such as Neurath, Schlick and Carnap, but also mathematicians such as Godel, also wanted to steer clear of metaphysics.

Coming to the Indian scene, it is hard to conceive of Hindu philosophy completely shorn of metaphysics. Hindu philosophers also had linguistic concerns, but their thoughts ran on different lines.

Grammarians such as Katyayana and Patanjali believed that language was eternal, very much like the Vedas. Speech after all, was the mode through which gods were invoked when Vedic sacrifices were performed.

Patanjali introduced the concept of ‘sphota.’ “Sphota is that which is manifested in the mind through the agency of hearing, and that which manifests meaning in the mind,” writes Dr. Pierre Filliozat.

Grammarian Bhartrhari (5th century C.E.) elaborated on sphota. When we say something, we enunciate all the letters in the sentence, sequentially. As each letter is uttered, the previous one fades away. How then do we get an idea of what is being said? This is where sphota comes in. Canadian scholar Harold Coward wrote: “Sphota is an object of each person’s cognitive perception.” Patanjali gave the example of the word cow — ‘go’ in Sanskrit. The moment the word ‘go’ is uttered, we get a mental image of a cow with all its features. Bhartrhari called the essence of speech ‘sabda.’ To him, ‘sabda’ is Brahman. Grammar helps us to see what errors have crept into language, and helps us to get rid of them. If speech is Brahman, then grammar is the path that leads us to this Brahman.

So while Western philosophy was occupied with language in a negative way, in India, language was looked at through a metaphysical prism.

My curiosity is aroused when I hear that a student of Western philosophy from Denmark, is doing his Ph.D in Saiva Siddhanta in the Sanskrit Department, University of Madras. I meet Mikael Stamm one afternoon, and he explains why he was disenchanted with Western philosophy. “I didn’t like its rejection of metaphysical questions. You don’t skirt round questions, simply because they are uncomfortable. I couldn’t accept the notion that it was the business of philosophy to clear up linguistic misconceptions for the sake of science. So I moved away from Western philosophy, and studied Computer Science, and for many years I worked in UNI- C, a government organisation, which develops service networks for Universities in Denmark.”

But the philosophical questions kept nagging him, and he thought perhaps India might have the answers. His first trip to India took him to Goa, and there he picked up a translation of the Bhagavad Gita. Reading it, he realised that the Gita had answers to many questions that had been troubling him. In subsequent trips, he visited many other towns, but when he went to Varanasi that things fell into place.

A visit to the Viswanatha temple and conversations with pandits there, helped him to make up his mind. He decided he would study Saiva Siddhanta, and applied to three Universities. Madras University was the first to respond, and Mikael did his Masters in Tamil Saiva Siddhanta.

He had read books on Hindu temples in Denmark, but had seen the temples merely as architectural marvels, without connecting them to the religion. It was his many visits to temples that made him realise that here was a living culture.

“In Denmark, our original culture was the Viking one, but within 200 years of the advent of Christianity into our country, the Viking culture was wiped out. So we don’t have an ancient, indigenous living religion and culture as in the case of Hinduism here,” Mikael says.

Tracing the history of Saiva Siddhanta, Mikael says, “The surfacing of distinct Saiva Siddhanta doctrines started at about 800 C.E. and lasted till 1300 C.E. After this, significant expressions of Saiva Siddhanta were confined to Tamil Nadu. The most important dualistically inclined Saiva Siddhantists were Sadyojyoti, Bhojadeva, Ramakantha and Aghorasivacharya, who based their views on the Agamas, especially the earlier ones such as Parakhya, Karana, Paushkara, Mrgendra, Matanga and Raurava. Aghorasivacharya was criticised by later Tamil philosophers such as Sivagnanamunivar and Śivaagrayogin, who were non-dualistic in their philosophy. But Tamil Saiva Siddhanta was not non-dualistic in a sense like Advaita, and the Tamil Saiva Siddhantists did not subscribe to the theory that the world was illusory.”

Mikael began studying Sanskrit from his very first day at the Madras University. Early lessons were self taught. Later, Dr. Balasubramaniam of the Sanskrit College, Mylapore, taught him Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra.

“I didn’t waste a minute. I would study Sanskrit from memory cards, while waiting for buses and in between lectures.”

Back home in Denmark, he studied under an Indian professor who also took spoken Sanskrit classes. From him, Mikael picked up an interest in Nada Karika, which is a text of 25 verses, written by Ramakantha II (11th century C.E.). It has a commentary by Aghorasivacharya. Nada Karika asks questions about the origin of sound, and how words relate to objects.

Does Saiva Siddhanta believe in Nada Brahman or Sabda Brahman? “No. In Saiva Siddhanta, Siva and Sakti are the ultimate sources. Word and sound are not present in the highest level, which is pure, without any trace of sabda or subtle matter. The ultimate experience is without words. This is opposed to the view point of grammarians and the view of later non dual Kashmiri Saivisim, where reality and language are one.”

Will he include a study of concepts like sphota in his work? “Yes, especially because I think concepts such as these deserve more attention from Western philosophers.” He plans to make a comparative study of Saiva Siddhanta with Nyaya, Mimamsa, and Bhartrhari’s work. He also wants to zero in on a temple and see how words are used in rituals. He wants to show how the history of the ritual and philosophy are connected.

Mikael says he left Christianity at the age of 25. “I lost faith in Christianity. I could not believe that you lived once and then went to heaven or hell. I also could not believe in Absolute Evil and Absolute Good, conquering the evil. I have seen how this is politically used, by labelling people evil. When I was a student, there were many Communists in my class. The government was quick to label them ‘evil.’ When the Communist movement lost its steam, a similar pattern was formulated. But the new evil became the immigrants. The only concern of the Danish People’s Party, for example, is to keep out foreigners. In India, I am amazed at how a religion, which predates Christ by a few thousand years, still survives although it is not patronised by the government. I see how many temples thrive, not because of government help, but because of the bhakti of devotees. In Denmark, the Church is run by the government and all priests are civil servants.”

Mikael says that a majority of youngsters in Denmark don’t go to Church, although Christianity is taught as a subject in schools.

Is his interest in Saiva Siddhanta more than just an intellectual one? “Of course. I am a practising Saivite. I have also become a vegetarian.”

Is it easy being a vegetarian in Denmark? “No, it isn’t easy. When I go to restaurants with my friends, the people in the restaurant have to scramble to toss a few vegetables together to make a salad for me. But luckily, there is an Indian restaurant in Copenhagen, where vegetarian food is served.”

After he finishes his doctoral studies, Mikael Stamm wants to teach Saiva Siddhanta in India, preferably in Tamil Nadu.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> Friday Review / by Suganthy Krishnamachari / June 16th, 2016