From a high-paying job to a home-made curry business and rearing indigenous cattle at home, G. Rajesh is living his dream

“What’s with you now? Don’t be scared, they won’t hurt you!” G. Rajesh chides his cow Singari. Summer is setting in with a vengeance and the grazing ground in Tambaram where Rajesh is cajoling his cattle to drink water, is blazing hot. Cut to five years ago, and the 34-year-old would’ve been seated in an air-conditioned office discussing mutual funds across the table, with a customer. Some decisions can tilt one’s world on its head and Rajesh’s did just that. A year ago, he decided to give up a high-paying corporate job and live life on his own terms.

The big leap

“I’ve always been angry with consumerism,” says Rajesh. “To have someone dictate terms, telling us what to buy, what to eat, and how to live our lives.” His 12 years of corporate life only furthered his dislike for all things “superficial”. “I was being judged based on the car I drove and the brand of pen I used,” he shakes his head. There was good money, but then Rajesh says that he’s the same person — whether he earned ₹ 8,000 or ₹ 80,000. “The more money I made, the more my needs increased.” He put an end to this constant struggle with his way of thinking and how society functioned, and started his own business.

Headquartered at his Tambaram home, Rajesh’s ‘Thamizhan Home-made Curries’ has five outlets around the area. His small team that consists of S. Madhusudanan (his business partner), M. Govardanan, R. Sridevi, G. Mithra, S. Deepa, T. Jayanthi, and M. Vaidegi, makes various curries that range from sambar and urundai kuzhambu, to prawn and fish curry, at their central kitchen, to be sold in the evenings.

“I’ve always wanted to run a business of my own,” says Rajesh. The idea of selling curries has been with him for a long time. “After an evening of shopping with my family, my father would say ‘let’s buy pakodas and manage dinner at home’. Or mother would say, ‘There’s sambar, let’s have dosas’.” A lot of people prefer a simple home-cooked meal after a workday or a day out, he feels. These are the customers he taps into.

Home-style food

Rajesh hopes his takeaway curries give customers the satisfaction of having eaten at home, and at the same time, reduce the time and energy spent in cooking. He says that the curries are made home-style, and that they are free from food colours and taste-enhancers. Rajesh plans to expand his business in the future if things go well. “But to ensure quality, the kitchens should be within a 10-km radius of the outlets,” he says.

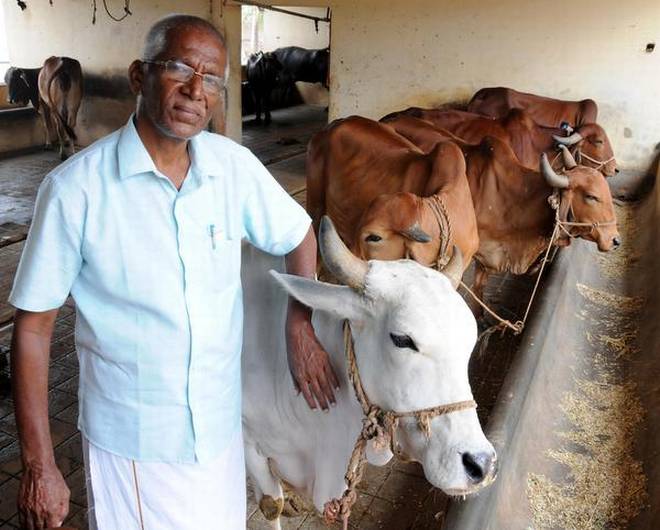

Enter Rajesh’s Tambaram home, and you are greeted by an interesting mix of smells — of the curries bubbling on the terrace kitchen, and that of cow dung. For in his backyard, is a cow-shed, where a noisy brood of chickens peck at the bushes by a well. The cows, Thangam, Singari, and Selvi, all from the Kankrej breed, have gone out to graze. “They’ll be back by 3.30 pm,” explains Rajesh.

Cattle love

He takes us to see them at the grazing grounds — with glorious horns and tinkling bells around their necks, the cows are beautiful. “I sell their milk to friends and family,” says Rajesh. The cows take up a lot of his time during the day, and his curry business keeps him occupied in the evenings.

But Rajesh functions at his own pace — he picks up his kids from school, has long conversations with like-minded people who drop in at his home over a delicious meal cooked by his mother…

In short, Rajesh’s day is in his hands and he can choose to do what makes him happy.

“This is why I gave up my job,” he says. “I might not save as much as I would’ve had otherwise,” he says. “But that’s all right. I’m able to practise sustainable living in my own way. I want to show that it is possible to live close to Nature as well as make a viable business out of it to take care of one’s needs.”

Rajesh has no regrets about leaving the corporate way of life. “Earlier, I would keep running; running to catch the train, running to meet my clients, just running through the day,” he says. “Now, I’m able to slow down. I read a lot, I’m able to grow a beard,” he laughs.

Here’s a shortfilm on Rajesh by Big Short Films

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society / by Akila Kannadasan / February 27th, 2017