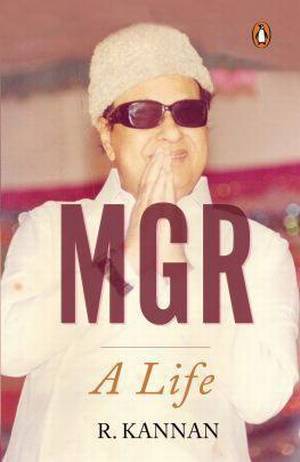

In his centenary year, a perceptive biography presents MGR with all his achievements and faltering, his personality and politics

M.G. Ramachandran never ceases to fascinate. In the 30 years since his death, there are signs to show that his popularity in Tamil Nadu has not declined. If a digitised version of one of his movies from the 1960s is released, it still runs to packed houses. It is his centenary year, and the same veneration that he commanded among his followers seems to prevail even among a generation that could not have seen him in his heyday.

R. Kannan’s informative biography brings out the major reasons for the MGR phenomenon: an everlasting reputation for charity, the trust he inspired in the masses that he stood for their welfare, and his carefully cultivated image as a do-gooder. What makes this a perceptive account is that it rarely descends to hagiography, and touches, albeit in a nuanced way, the man’s undoubted shortcomings.

Early episodes in MGR’s life accounts are revealing. Much of this part is perhaps drawn from MGR’s own memoirs and from contemporary accounts, but what Kannan offers is the first cogent narrative of MGR’s early years, the debilitating poverty in which he grew up, the role of his mother and brother in shaping his outlook in life. The portrayal of Ramachandran’s poverty-stricken life as a child theatre artiste makes for a moving read. Too poor to go to school, he and his brother lived through ordeals and torments in a theatre company as they had no other means of livelihood. MGR had early exposure to both the survival throes and the petty jealousies of an incipient theatre and cinema career. These experiences informed his welfare-centric policies several decades later as chief minister.

Tinsel world stories

Many pages are devoted to MGR’s experiences in the tinsel world, understandably so, as this was the medium that was used to project his image. Initially used by the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam to draw crowds, he was somehow catapulted into the political limelight due to various factors. His mentors in theatre and politics were not his only influences. Even those who saw him as a threat and still others who underestimated his rise in the party, were also indirect motivators for his aspirations.

Almost all of MGR’s film songs were written with an eye on his emerging political career. Even though this is well known, the author’s engaging account — as well as free-wheeling translations — of the various songs that made him a hero, a revolutionary, a friend of the masses, a philanthropist, a teetotaller and the scourge of evil, helps in understanding the direction in which he was heading in politics.

There is a lot about his career in cinema, but somehow, there seem to be too many details about how he signed up particular films and how he landed a certain role. There is not enough about many other aspects of his film career, including his directorial ventures and his insight into various trades in the industry. Given the build-up in the biography about his career trajectory, the account of his three successive stints as chief minister can be seen as sketchy. As this part is narrated mainly through public events and major political developments, the reader does not get a full insight into the functioning of MGR as an administrator. At the same time, the author does convey the essentials. One gets a sense of how MGR did not believe in the core Dravidian principle of rationalism and opposition to religion, of how he lived in perpetual fear of the Centre and how tax investigations influenced his political decisions.

Chief minister’s diary

As chief minister for 10 years, he relied on intuition and the unique connect he had with the masses in making major announcements. Of course, there were blunders and long phases of inactivity, economic and administrative stagnation and political uncertainty because of his bouts of illnesses. The transition from a person who managed to run a relatively clean government to one who allowed corruption to acquire huge proportions has been captured. The extent to which the liquor trade and the privatisation of engineering and medical education contributed to it is amply clear in the account.

Nearly a century ago, E.M. Forster contrasted the western or English character with that of the easterners. “The Oriental has behind him a tradition of kingly munificence and splendour,” he wrote, contrasting these qualities with the “middle class prudence” of an Englishman. Forster would have been delighted had he met someone with MGR’s reputation for munificence.

But MGR had other qualities that monarchs are famed for. He rewarded loyalty and punished disloyalty. He rarely brooked dissent, although political heavyweights within his party did take him on occasionally. Farmers and government employees, political rivals and the media, all bore the brunt of his authoritarian style, although he sometimes tried to balance the strong-arm tactics with occasional sops. He was whimsical to a fault, once attempting to undermine caste-based reservations by introducing economic criteria and then rolling back the decision and raising backward classes quota from 31% to 50%. This biography does not miss any of this.

When writing about a larger than life figure, one tends to place more emphasis on the aura and mythology around the person and less on the man himself. R. Kannan manages to tease out a balanced picture of the man, with all his idiosyncrasies and foibles, his achievements and faltering, his personality and politics.

MGR: A Life; R. Kannan, Penguin Random House, ₹499.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Reviews / by K. Venkataraman / September 16th, 2017