I’d always thought there was only one renowned Vedanayagam, a Tanjore Christian who expressed Christian thought in words sung to Carnatic music, a man of Tamil letters but who was known by two names: Vedanayagam Sastriar and Samuel Vedanayagam Pillai. Sriram V set me — and several others — straight recently on Pillai, telling us that Sastriar was a totally different person, born 50 years earlier. The straightening out offers me this opportunity to clear the air about the confusing Vedanayagams.

Sastriar, born in 1774 a Roman Catholic in Tirunelveli, became a Lutheran, converted by the Rev Christian Schwartz, the tutor of Serfoji, heir apparent of Tanjore. Sastriar joined Serfoji in his classes and they became friends. Sastriar then went to study Theology in Tranquebar, at the seminary of the first Protestant Mission in India.

While working in Mission schools in Tanjore, he began composing Christian lyrics to Carnatic music and writing Christian treatises. He was to write over 125 treatises during his lifetime, his best known the Bethlehem Kuravanji.

When Serfoji became king, he made Sastriar his Court Poet. And Veda Sastrigal, as he became known, continued composing hymns and songs in praise of the Holy Trinity. This emphasis led to his falling out with the Court of Tanjore, but had him considered as the first Christian Evangelical Poet.

The other Vedanayagam, Pillai as I’ll call him, is known as Mayavaram Vedanayagam Pillai. Born in Tanjore in 1826 a Roman Catholic, which he remained all his life, he got employment in the law courts in Trichinopoly after schooling. While working, he studied Law, passed the necessary exams and was appointed a Munsif in Mayavaram. Thirteen years of dedicated service later, he resigned when a new District Judge was appointed; a sick Pillai had not gone with the other sub-judges of the district to welcome him, an act misconstrued enough to cause differences with his superior. Early retirement gave him time for two fields he had become interested in — writing and Carnatic music.

After translating several law books, he wrote a book he is still known for: Neethi Nool (The Book of Morality). Written in Tirukkural style, its couplets are on moral behaviour.

Then, in 1879, there appeared the book that would make a difference to the Tamil literary scene. Titled Prathapa Mudaliar Charithram, it is considered the first Tamil novel. In a preface to later editions, he explains, “My object in writing this work of fiction is to supply the want of prose works in Tamil, a want which is admitted and lamented by all.” He also says his previous books were rich with “maxims of morality”, in this he was illustrating them with examples from life. This lengthy book focuses more on instruction in values than entertain as a romance. In 1887, his second, and last novel, Sugunambal Charitram, was published, but was not as successful. He wrote 14 other books.

Moral education is what Pillai brings into his huge collection of songs. These songs, composed to no particular deity, are still popular in Carnatic Music concerts. In fact, Sanjay Subrahmanyan not so long ago gave an entire concert featuring Pillai’s Carnatic compositions.

***

* Bhaskarendra Rao Ramineni who scours the Andhra Pathrika archives tells me that an obituary of Yakub Hasan says his wife Khadija Begum was a Member of the Madras Assembly and that Rajaji, paying tribute to his Public Works Minister in his 1937 Ministry, said that Hasan’s wife was from Turkey.

That gives a clear cut answer to my speculation in Miscellany, December 4. Bhaskarendra also sends me a picture from the paper showing Khadija Yakub Hasan in Western clothes, a reflection of Ataturk’s modern Turkish women. Yakub Hasan, a founder of the Muslim Educational Society, represented the Muslim League in the Madras Legislative Council from 1916 to 1919. Later, he represented in the Council the Chittoor Rural (Muslim) constituency from 1923 till 1939. As Minister in charge of the PWD he played a significant role in the negotiations with Hyderabad on the Tungabadhra Project. He convened and presided over the first Khilafat Conference (1919) held in Madras and resigned from the Assembly over the Anglo-Turkish treaty (1920) which ended the Khilafat campaign to restore the Caliphate.

***

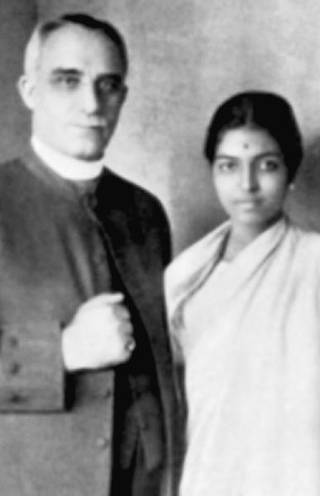

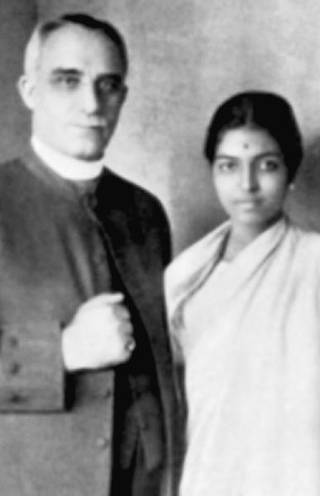

* Who was the Arundale that Rukmini Devi married, asks T Saroja, in a letter about the Music Season, visitors from abroad and what they’d think of Kalakshetra’s problems. Arundale was no visitor to the Music Season; in fact, there was no Music Season when he arrived in India. George Sydney Arundale was a Theosophist from Australia whom Annie Besant had invited to head the educational programme in the Theosophical Society’s campus. The 16-year-old Rukmini Nilakanta Sastri (whose father was a Theosophist) met the 42-year-old Arundale and they fell in love, getting married in 1920, scandalising Madras Society. Whatever the criticisms about this Spring-Autumn marriage, together they were to change minds with their contribution to the classical dance scene in Madras. During a visit to Australia in 1926, they went to see Anna Pavlova dance. It was later said, Rukmini Devi was “a changed person from then … she wanted to be a part of the fascinating world of movement and expression.”

From that desire was conceived Kalakshetra, the premier school for South Indian classical music and dance. Does it really have to cope with politicking casting a shadow over it ever since the passing of Rukmini Devi in 1986?

The chronicler of Madras that is Chennai tells stories of people, places, and events from the years gone by, and sometimes from today.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> News> Cities> Chennai> Madras Miscellany – Chennai / by S. Muthiah / December 18th, 2017