St. Thomas is largely credited with bringing Christianity to India

When Reverend Father P.J. Lawrence Raj was an assistant priest in Chennai, he wrote many letters to the bishops of the Catholic world. When he didn’t get a response, he wrote to Christian magazines.

His letters were an attempt to solve a new-age problem afflicting a historical icon: in a saturated religious marketplace, he was seeking brand recognition for St. Thomas, one of the 12 apostles of Jesus and the man largely credited with bringing Christianity to India through the Malabar coast in 52 AD.

Fr. Raj composed these letters over 30 years ago, on St. Thomas Mount, a hillock overlooking Chennai’s airport. Two thousand years ago, when there was no airport, no flights roaring overhead, and when most of the surrounding land was dense forest, it is believed that the apostle Thomas was murdered by a group of Hindus who did not fancy his proselytising.

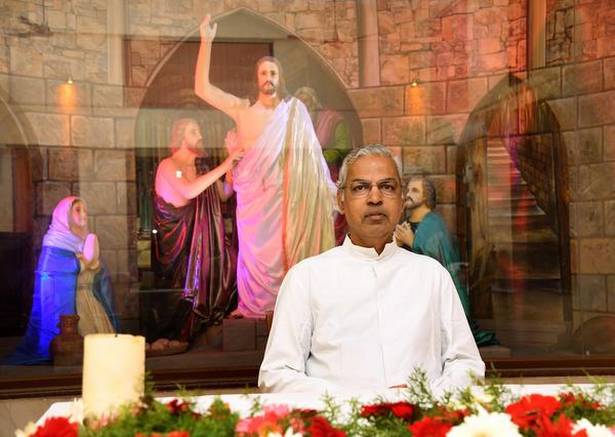

“I have a special attachment to him,” says Fr. Raj. “He was a great witness for faith. We are all Doubting Thomases — we don’t believe easily.”

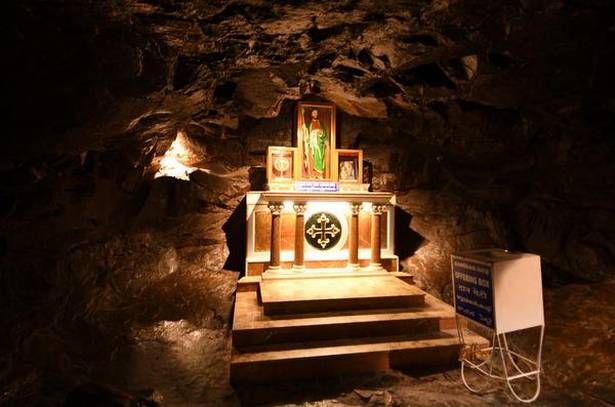

Fr. Raj, who was ordained 36 years ago, has served at some of the Ivy League institutions of Chennai’s Catholic world — Santhome Basilica, where Thomas is buried; Velankanni Church, dedicated to Mother Mary, and now Little Mount, where the apostle is believed to have hidden from his murderers inside a grotto.

Thomas is believed to have lived, and preached, in the Chennai region for over 13 years. As one of the original Twelve, he has built-in brand recognition. There are churches, roads and even hospitals named after him. But of late, he is no longer the draw he once was; festivals dedicated to his memory are in the shadow of others, notably the Velankanni festival, which draws the faithful in their thousands.

Neglected saint

“Two thousand years is a long time,” Fr. Raj muses. “What happened after St. Thomas was martyred and till the Portuguese came, we don’t know. The Portuguese gave more importance to Our Lady. To be very frank with you, it is the people of Kerala who are more attached to St. Thomas; they call themselves St. Thomas Christians. In Tamil Nadu, we have more of an attachment towards St. Francis Xavier, or recent saints like Mother Teresa. And when Velankanni Church came up in Besant Nagar in the 1970s, our devotion to Our Lady became stronger. Perhaps priests didn’t take the initiative, but I think we have neglected St. Thomas.”

Fr. Raj’s efforts to bring Thomas back to the mainstream narrative of Chennai’s Roman Catholic world reads like a marketing campaign: High-level initiatives include a renovation, in the early 2000s, of the Santhome Basilica where the remains of the apostle were buried in a crypt below surface level. Members of his parish nicknamed him ‘Father Renovation’ as he orchestrated a slew of beautification and restoration projects in his parish churches, including St. Teresa’s Church in Nungambakkam, even as he faced allegations of corruption and misappropriation of funds. “I tell people that ‘that this tomb of Thomas is the womb of Christianity in India’ — without Thomas, Christianity would not have come to India so early, and here at Little Mount, I am trying to do the same work I did at Santhome.”

Outside, on the sloping grounds of Little Mount Church, a short-statured, elderly man dressed all in white with a black belt takes up the story. D’Cruz knows four languages, and claims to have a connection with Thomas “that nobody else has”.

The church’s local guide steers you in the direction of the grotto, pausing to point out the spots where Thomas placed his hand, his foot, his knee. Gesturing at a narrow opening in the cave, he says, “This was not an open space, but when Thomas prayed and needed to escape, it opened up.”

Reviving Thomiyar

He ticks all the boxes: the bleeding cross, the holy fountain where Thomas quenched his thirst during those last hours (whose water is now sold in plastic bottles for a nominal fee), and even tells me a slice of his own personal story. “For me, it is 100% Jesus,” D’Cruz says. “He and the Mother have brought me to Thomiyar.”

He sees a group of Korean tourists approaching, and breaks off our conversation. “Excuse me, over here!” he calls out, in suddenly accented English. “Do you want to know about Thomas?”

D’Cruz is a grassroots ambassador for Thomas, and fits in with Fr. Raj’s plan to make the apostle relevant again. His compatriot Aubrey Laulman, an Anglo-Indian who started working at the church eight years ago, after settling his daughters in marriage, performs a similar function at St. Thomas Mount. He says he was hesitating on the steps leading up to the mount when he felt a gentle but irresistible push on his shoulder. “It was a miracle,” he says, drawing my attention to the cross believed to have been hand-carved on the rock by Thomas himself.

“Look at it from different angles, you will see how intricate the work is,” Laulman points out. “Those days, people prayed a lot. That’s why Thomas was able to do so many miracles. They prayed a lot because there was no Tata Sky,” he says, laughing at his own punchline, the sound of his delight bouncing off the empty walls of his church. “Don’t mind me, I am very frank.”

D’Cruz and Laulman are spreading the story of St. Thomas among those who visit the two churches, but Fr. Raj’s focus is on those who don’t even make it as far. “After I took over the parish two years ago, we have made The Feast of St. Thomas an 11-day affair, not three,” he says, as we pick our way gingerly across the debris of building work. “We are renovating the entire church; we will make the festival as popular as The Feast of Our Lady, which is celebrated after Easter. It is time to focus our attention on St. Thomas, to give him publicity, and get the parishioners and the public involved in the story.”

This essay is from a National Geographic Society and Out of Eden Walk journalism workshop.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> Field Notes> Sunday Magazine / October 27th, 2018