Bridge-building tales

As promised last week, here are a couple of tales about the building of bridges in 19th Century Madras as related to me by civil engineer D.H. Rao who has made delving into the histories of the city’s bridges his hobby. These are stories arising out of Government’s practice of getting estimates for civil work and then finding the costs have been exceeded. Inquiries follow, then as now, but what happens next? Nothing seems to change.

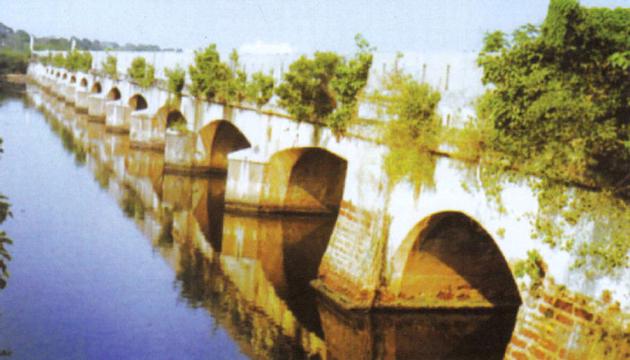

In the case of the 1840 18-arch Elphinstone Bridge over the Adyar (now lying derelict but looking solid, while constant maintenance work goes on on its neighbour, the new Thiru Vi Ka Bridge), on its completion, the Military Board declared it a magnificent piece of work. But Governor Lord Elphinstone did not think so; he wanted to know from the Board why the cost had exceeded the estimate, particularly when it had been approved by the Court of Directors in London with the proviso that the approved amount should on no account be exceeded.

In his reply, the Superintending Engineer cited the costs of two other bridges he had built to show that the costs incurred in building the Elphinstone Bridge were on the same lines. The extra cost incurred was only because the river was always full of water and several persons had to be employed in constantly bailing out the water to keep the coffer dams dry while raising the foundation. This was totally unexpected. The arguments went on for months, but in the end the matter was happily resolved to the engineer’s satisfaction.

It was in another instance too, but in this case it caused the builder of the 1805 St. George’s Bridge (now the Periyar Bridge) considerable more concern for months. Lt. Thomas Fraser was not only censured for the cost over-run but also had his commission and other benefits withheld. In this case, Fraser justified the excess expenditure by pointing out that after the foundation work was completed, he was asked by the Council to re-align the bridge. So, he once again had to sink wells for the foundation, piers and abutments. Further changes were ordered by the Council from time to time and he carried out the Council’s orders every time. He was therefore not responsible for the final cost — which was entirely due to his only having carried out the orders of the Council. In this case too, the arguments continued for long, but eventually Governor Lord William Bentinck accepted Fraser’s appeal and restored all his benefits.

On a third occasion, a bridge on South Beach Road needed substantial repairs. These were carried out, but a couple of years later the Military Board sought further funds to carry out additional repairs to the bridge. The Governor was not ready to sanction the amount until he was told why the bridge had not been regularly inspected for maintenance, who was responsible for such inspection, and “why he had not carried out his work sincerely.” What eventually happened in this instance is not known, but what is clear is that, at one time, heads of government kept a sharp eye on even comparatively minor expenditures. But then those were more leisurely times, weren’t they, and heads of government had time on their hands.

*****

A reluctant sale

Some time ago I had mentioned in this column that the land on which the handsome Egmore Railway Station (then of the South Indian Railway) was built had belonged to Dr. Pulney Andy (Miscellany, September 20, 2010) and that he had sold it for Rs.1,00,000 to the SIR in 1904. It wasn’t a particularly happy sale, I now learn from a copy of Dr. Pulney Andy’s letter to the Deputy Collector of Madras, J.R. Coombes, which was sent to me by a reader from ‘Trichinopoly’, N.C. Martens. The land in question was 1.83 acres in extent and had several buildings on it. It was his attachment to those buildings that were the cause for the reluctance of ‘S. Pulney Andy M.D., M.R.C.S. (Eng.), F.L.S.’ to sell the property, the letter of ‘15th February 1904’ makes clear.

Reacting to a letter from the Deputy Collector citing ‘Act I of 1894’ requesting his property for “the remodeling of the S.I.R. Egmore Station”, and asking whether he had any objections to handing it over to the S.I.R., Pulney Andy writes, “I have very strong reasons for not wishing to part with my property…” He goes to state those reasons.

He writes that he had bought the property “mostly for the benefit of my health which was broken down after long service in the Travancore state… (and the environment proved itself over) about 30 years… not a case of any illness or death occurred among the dwellers on this estate.”

Secondly, the house was designed and built by his wife before she passed away in Travancore, after which he returned to Madras to spend the rest of his life in the house “which perpetuated her memory” and which he had improved by developing an orchard around it.

Then comes his most significant argument. “After retiring from Government service, I have turned my mind to the remodeling of the Indian Christian Church and am the founder and the President of the National Church of India. My residence in Egmore is the Head Quarters of the movement and I have utilized a building here for the purpose of worship and there have been already two ordinations of Ministers during the past year. It was also my intention to erect a substantial building as a Temple for public worship by members of the Christian Community on the land… (which) is centrally located.” With such extent of land not available in a central area, a move to a distant location where space might be available would inconvenience his congregation considerably, Pulney Andy goes on to explain at some length. He, however, concludes:

“But should it be considered that my property is absolutely required for the purpose of Railway construction and should Government desire to compel me to part with it, under the provisions of the Act, I beg to state that I may be granted a compensation of not less than one hundred thousand rupees (Rs.100,000) for it and sufficient time should be given me for removal.” His request was met with alacrity but not generosity, the ‘not less’ ignored, it would appear, for the handover was quick and the station was ready to flag out its first train, the Boat Mail, on June 11, 1908.

*****

Search for the Old Jail

Where is or was the Old Jail, wonders Jayanthi Selvam, saying she uses Old Jail Road quite often. The road is the central portion of a three-part road, from east to west being Ebrahim Sahib Street, Old Jail Road and Basin Bridge Road in the southern shadow of what was the North, or Old Town, Wall, of which only the stretch preserved with the Maadi Poonga atop it is all that survives. It was south of a bastion of this wall that the Old Jail was established in 1804, though its roots go back to 1692.

The Old Jail’s premises, at the corner of Popham’s Broadway and Old Jail Road, was cleared of prisoners shortly after Independence and the campus was given to the Congress Prachar Sabha which ran a cottage industries training centre in the numerous buildings there. When Kamaraj stepped down as Chief Minister in 1963, the enthusiasm for the training centre waned and the premises were handed over to the Central Polytechnic Institute and a new Arts College for Women in 1964. Four years later the last of the CPI’s constituent units moved to Adyar and the college expanded into the Bharathi Women’s Arts College. It was many years before the College got new buildings for its students, its early batches having used many a prison block, some of which survive, derelict, till today.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus / by S. Muthiah / October 19th, 2014