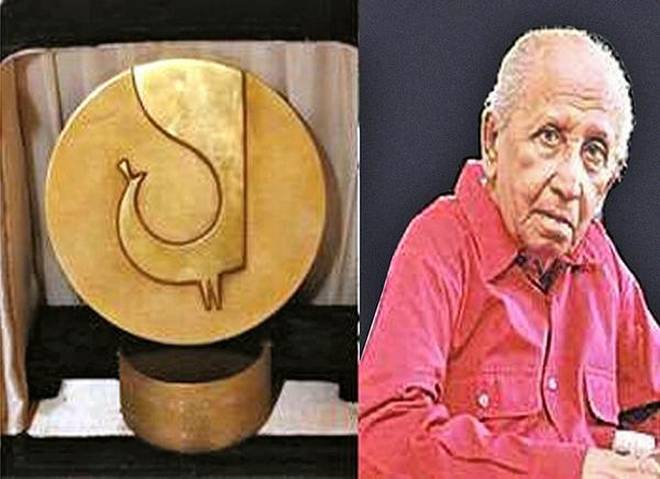

The death of Lester James Peiris, the father of the ‘New Sinhala Cinema’, brings back to mind his winning in 1965, with his Gamperaliya (The changing village; 1963), the first Golden Peacock awarded and for taking Sinhala film-making not only out of Madras State studios but away from the clichétic Tamil film formula.

Lester was the London Correspondent of The Times of Ceylon when I was its Foreign News Editor in the 1950s. We were in regular touch during that period, when he was experimenting with film-making. When he returned to Ceylon he opted out of journalism and focused on cinema — first with government documentaries and then the making of a new kind of Sinhala film, one drawing inspiration from the realism of Italian and French films. We kept in touch, however, because Iranganie Serasinghe and Sita Jayawardana were two of his leading supporting actresses, both girls who worked with me in features and who were forever asking for time off for ‘shooting’ or who kept dozing after ‘night shoots’. But when I moved to Madras I lost touch with Lester whom many consider one of the greatest South Asian film-makers.

Lester made 20 full-length feature films and about a dozen documentaries and short films. He started with a winner, Rekawa (Line of Destiny, 1956), which focused on village life. It was the first Sinhala film to be shot entirely in the country and the first to be shot mainly outdoors. It was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the 1957 Cannes Film Festival. Gamperaliya, for its part, was shot entirely outside the studio. Besides the Golden Peacock, it also won Mexico’s top international film festival award.

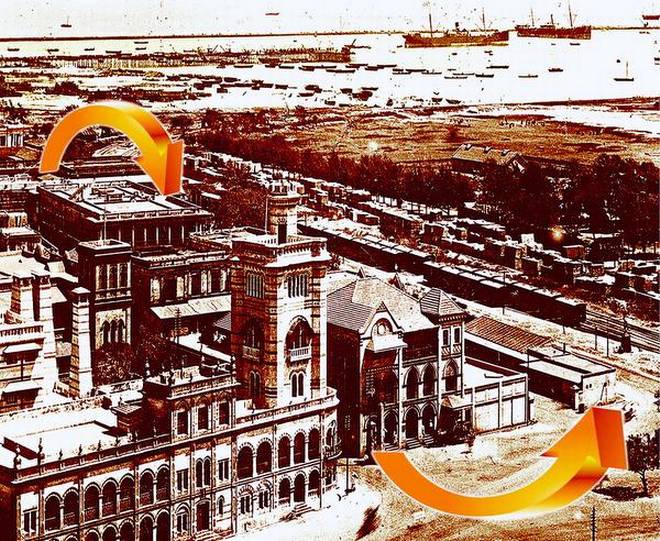

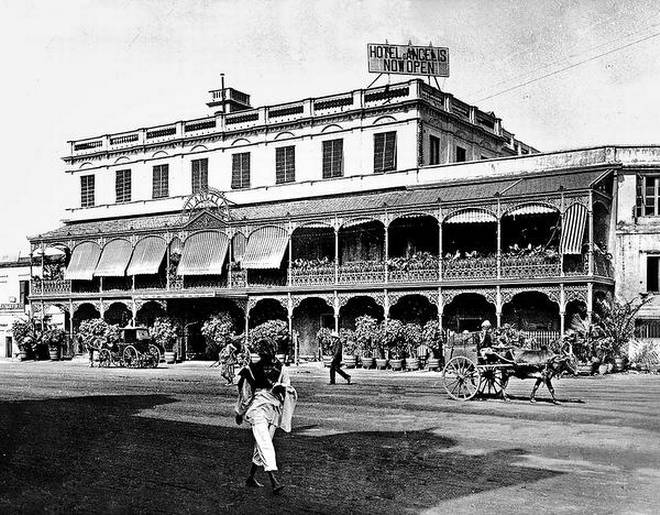

The first Sinhala film to be made, Kadavanu Porundhuva (Broken Promise), was shot entirely in Madras and released in Colombo on January 21, 1947. It was produced by S M Nayagam, who was what they called in Ceylon an Indian Tamil (being from the Tamil districts of Madras Presidency) and who not only pioneered the making of Sinhala films but also the starting of local industries. The film was directed by a Bengali, Joti Sinha. This was followed by 42 other Sinhala films being made in Madras, Coimbatore and Salem. It was only in the 1950s that Sinhala films began to be made in Colombo, where Nayagam had established the first studio. But even then, till legislation in the late 1950s, technicians from Madras continued to work in Ceylon — and the generation of Sinhala technicians who followed them benefited considerably from their mentoring.

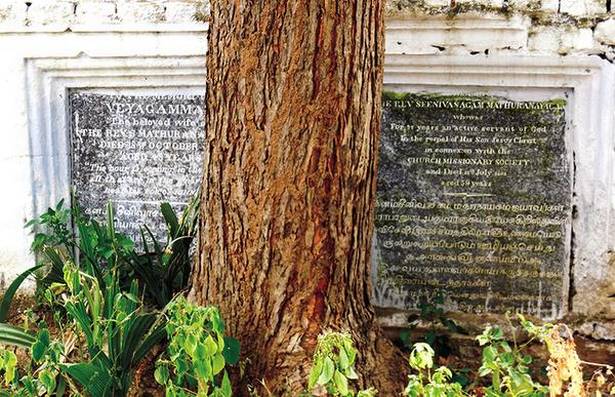

One of the earliest from Madras to direct Sinhala films was Anthony Bhaskar Raj. Lenin Moraes was another director from Madras where he had learnt cinematography and make-up. J A Vincent was Art Director for over 100 Sinhala films after starting out with Asokamala being made in Central Studios, Coimbatore. Another connected with Asokamala was experienced cameraman Mohamed Masthan who also shot Sujatha in Salem. When he moved to Ceylon, he was guru to a generation of Ceylonese cameraman. He later went into direction. Other directors from Madras to work in Ceylon included A S A Samy, P Neelakantan, L S Ramachandran who pioneered Sinhala films on village life, and A S Nagarajan. After having been a scriptwriter in Madras, Nagarajan moved to Ceylon and into direction. Among his films was Mathalan, based on the Tamil hit Mangamma Sabatham.

Starting from where the Madras technicians left off, Lester James Peiris gave a completely new face to the Sinhala film industry. R.I.P., Lester.

________________________________

They mined for diamonds too

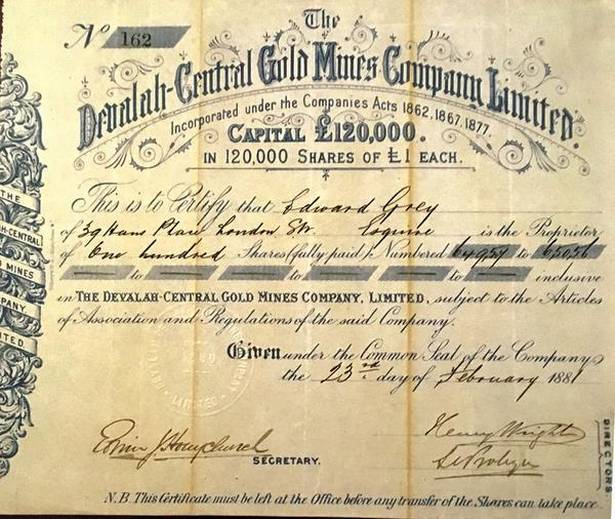

My scrip-collecting correspondent, Sayeed Cassim, has sent me some fascinating material, responding to my gold rush story (Miscellany, April 23). The best of it is a share certificate issued by the Devalah (Devala) Central Gold Mines Company Limited in 1881. This was one of the first companies to be established— even before the gold rush began — and, as I had recorded, it was promoted by Parry & Co, though the certificate (my enlarged picture today) gives no indication of that.

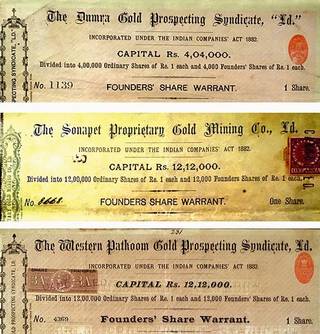

Accompanying it are the headings of three other certificates, those issued by the Western Pathoom Gold Prospecting Company Limited, the Sonepat Proprietary Gold Mining Company Limited, and the Dumra Gold Prospecting Syndicate Limited. Having made a study of these three certificates, Sayeed Cassim feels that “these were companies set up only to rake in the money and hoodwink the public.” He bases his presumption on the fact that there are several identical features in these certificates which “make their intentions suspicious”. He lists the following:

Similar authorised capital of each of these companies:

Date of all issues very close together in 1890

Printer the same: Calcutta Catholic Orphan Press;

Per value of each share only one rupee (to induce greater subscription?), and

Certificates of Western Pathoom and Dumra signed by the same person.

But that is not all. Apparently there were optimists who thought that there were diamonds in the hills too and companies were formed to prospect for them. He names The Madras Diamond Mining Company Limited and The Madras Presidency Diamond Fields Limited. Were they genuine speculators or in it for the quick buck?

If you want to take a better look at these certificates, Sayeed Cassim suggests you have a look at the website of David Barry of London (www.indianscripophily.com), who has “the largest and finest collection of Indian share certificate in the world.”

The chronicler of Madras that is Chennai tells stories of people, places, and events from the years gone by, and sometimes from today.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> History & Culture> Madras Miscellany / by S. Muthiah / May 14th, 2018