Tamil Nadu erupted in the early 20th century into what can only be called a revolution, the Dravidian revolution, which transformed the texture of Tamil society. It was ‘Periyar’ E.V. Ramasami Naicker, who changed the classist nature of public life in Tamil land. Within a generation, Tamil Nadu was transformed; with people from various castes taking control of politics and society; the ‘Periyar’ effect.

In this avalanche of change, Brahmins who were at the top of the social food chain became the singular targets of the new revolutionary correctives. But in a small corner of the beleaguered Brahmin world of Tamil Nadu existed two art forms — Carnatic music and Bharatanatyam — which became a new sanctuary for the Tamil Brahmin, very specifically, the Mylapore Brahmin, unmistakable as the ‘Mama’ of Mylapore, Madras’s most famous temple-suburb.

In the winter of 1927, a historic session of the Indian National Congress was held in Madras, presided over by Dr. M.A. Ansari, at which, on the motion of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Purna Swaraj or Independence was accepted as the objective of the Congress.

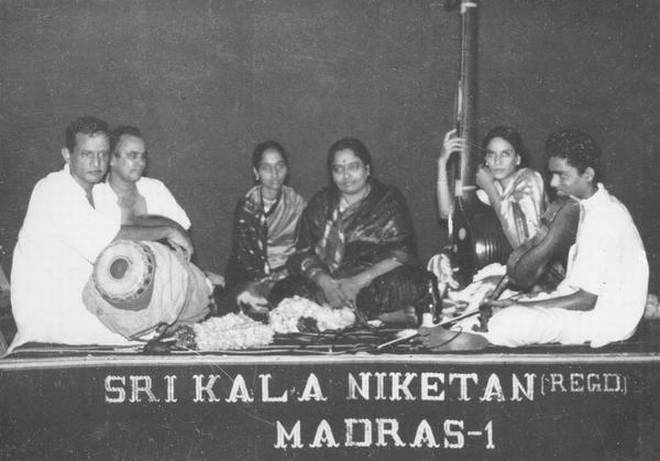

The session was also historic for the music community in Madras because of the series of music and dance performances organised alongside. The very next year, Madras Music Academy was established for the “further advancement” of Carnatic music and to conduct music conferences and performances. And December became the chosen month, the one month in the year that Madras calls ‘cold’ and when the monkey caps come out.

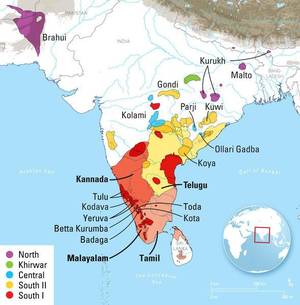

Madras emerged as the ‘classical music place’ to be in within the first half of the 20th century, and a number of music-saturated Brahmins homed in on the city. In bygone centuries, Carnatic music was spread around the towns and villages of Thanjavur and Tirunelveli but it was now concentrated in cosmopolitan Madras. Here the art form was reorganised, systematised and intellectualised. Madras became the Mecca of Carnatic music.

By the 1980s, people from across India were heading to Madras every December. There were over 15 sabhas and leading musicians performed in almost all of them.

Through this period, the government was filled with leaders who took forward the anti-Brahmin legacy. But that did not matter when it came to celebrating the December festival.

Chief ministers and governors inaugurated sessions of Carnatic music and acknowledged its great aesthetic strength. Rationalist leaders and atheists didn’t blink an eye when speaking at events, though Carnatic music was lyrically religious. Carnatic music and Bharatanatyam became examples of the cultural refinement of the Tamils, and musicians and dancers were celebrated as cultural ambassadors.

Enter, the hero

Paradoxically, a state that insisted on social equality came to be known nationally and internationally for two art forms practised, promoted and patronised only by the cultural elite.

From this rather serious sociological narrative emerges one person, a charismatic and entertaining embodiment of a societal overhaul. With his sheer presence he bestows upon Carnatic music its antiquity, at the same time containing it within his own identity.

He is today an ignored social animal, but when the sounds of the tambura waft through the humid Marina breeze, his face lights up, shoulders broaden, the space becomes his to own, he is on home turf, a turf he understands better than any curator, one on which he has watched so many masterful innings. The players and audiences look up to him, as he gives to the art as much as he receives, or so he believes.

Our hero is the Brahmin man, the chief patron of Carnatic music in Chennai. But he is not just any Brahmin man; this person is special, the hard core ‘Carnatic-ite’. We call him the Mylapore Mama. He has lived for centuries, probably saw Tyagaraja sing on the streets of Thanjavur, discussed the nuances of ragas with Konerirajapuram Vaidyanatha Bhagavathar, and bemoaned the death of Vina Dhanammal in the early 20th century. He is the typical Brahmin but wait, he is much more.

The essence of Todi

He proclaims, “I have music in my blood. After all, I grew up drinking Cauvery water.” Most of these Mamas seem to have had ancestors who lived around Thanjavur. He walks around Chennai the way his great-grandfather would have ambled on the banks of the Cauvery. He is great friends with the maestros, usually addresses them by first name, and even teaches them a thing or two about singing.

His essence is Kamboji, Kalyani, Todi and Kedaragoula. Within his mind exists the collective wisdom of the last 150 years of music.

He is, therefore, someone who has lived with Carnatic music from its times as a triangular (Brahmin, isaivellalar and devadasi) social preoccupation to its present singular Brahmin obsession.

He has seen all the changes of the 20th century and discussed its pros and cons, probably sniggered at them, and held on to what he believes are the core values of Carnatic music. Don’t think he is antiquated. He is not; he will surprise you with the most bizarre acknowledgement of a musician you thought was awful. You cannot slot him, he will deceive you, be careful. His greatest function has been as Carnatic connoisseur, the person who shapes the music and the musician, or so he believes. He will stroll into concerts, discussions and lectures and find his way out, all the time exuding an air of great superiority.

Metaphor for music

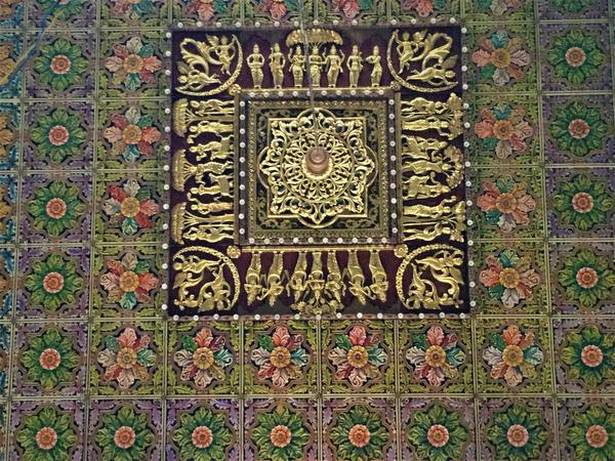

Why Mylapore? Because Mylapore is not just a Brahmin-dominated location in Madras (sorry Chennai); it is a metaphor. A metaphor that conjures up images of a man with a tuft, betel nut in mouth, bare-chested, clothed in a veshti. But these images themselves are metaphors, circles within circles. All Mamas don’t dress this way, but they retain the qualities that these images imply: traditionalism, comfort, belief, knowledge and control.

The Mylapore Mama has great command over the Queen’s language, though with a strong Sanskrit accent. He reads The Hindu over a cup of filter coffee, has strong opinions about everything, and, of course, can reel out the names of ragas, talas, compositions and — to the amazement of all — render snatches of several ragas. It is sometimes difficult to understand him as the words escape arrogantly from the corner of his mouth, the one-liners are cryptic, the words loaded and the sarcasm natural. Today, Mama may live in San Diego, Melbourne, Singapore, London, Delhi or Johannesburg but he is after all from Thanjavur.

Usually addressed as Shankar Mama, Sundaram Mama, Ramamurthy Mama or Krishnan Mama, these men are the custodians of Carnatic music.

Bearing that great responsibility, they operate differently with different people, and it is this that I find most fascinating. As in any field, there are always musicians at different levels of acumen and status; all of them build relationships with the Mamas.

Now put the Mama and Chennai’s music season together and we have a potent combination. The Margazhi Season is the Olympics of Carnatic music. The Brahmin music world assembles from around the globe to witness the show and Mylapore Mama is the mascot. It is his time to rule, dictate, pontificate, control and deliver a verdict.

A careful structure

The music season itself is structured in an interesting fashion. The organisation, the concert timing, the duration and venue influence artists and audiences, and together determine the artist’s status within the establishment.

As a general rule, mornings are devoted to lec-dems or concerts by super-senior musicians. Super-seniority is not equivalent to super-speciality; it only indicates the average age of the artist. Yes, there are also some greats, but the majority fall into the purely geriatric category. Over the years, this has changed a bit with younger artists also performing in the morning. The mid-day concerts are by novices and first-timers. After 1:00 pm is for artists a little more mature, which means they have performed at the mid-day level at least a few times before. These last till 5 p.m. roughly, with entry free for all.

The evening concerts are, of course, for the ones who have made it, the stars, the popular artists, to listen to whom people are willing to spend money. These hierarchies have been in play for decades and every musician hopes and prays to move from mid-day to evening concert. This is the equivalent of the Bollywood box-office dream.

These timings are also referred to in terms of the artists’ seniority: junior, sub-senior and senior, and each category is called a ‘slot’. Everyone — and I mean everyone — wants to know your slot and based on that decides your status in the Carnatic world.

(To be continued…)

The writer is a rebel, whether against cultural conventions or injustice or just bad tea.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society / by T.M. Krishna / January 06th, 2018