In the past few weeks — as well as at a celebration — we’ve heard much about the splendid growth of the Chemplast Sanmar Group from scratch 50 years ago and of how over those years it had nurtured and then been nurtured by N Sankar, whose first job, unpaid apprentice, was on the day Chemicals and Plastics India opened its doors. To me, the happiest part of that success has been how the Group has returned much back to society, promoting education and training, community welfare and healthcare, greening and nature, sport and art, and even saving failing journals like Madras Musings. But one thing I missed in all this was the seeding of the group.

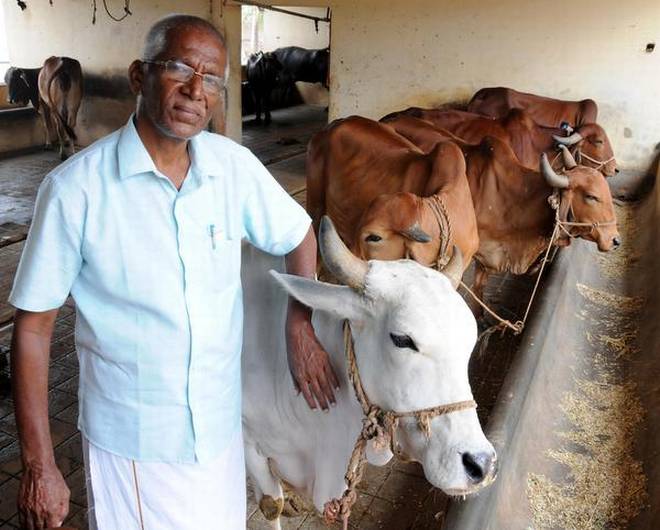

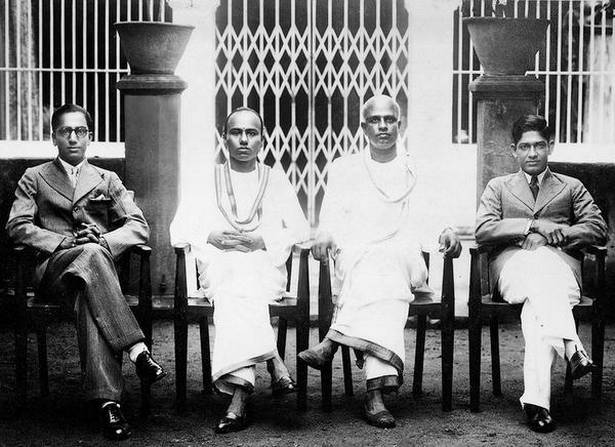

Those seeds were first sown in the back of beyond, in the village of Kallidaikurichi in Tinnevelly District when Nanu Sastrigal entered textile retailing, then moved into financing. His eldest son SNN Sankaralingam Iyer took the business further and with landowners in Tanjore helped found the Indo-Commercial Bank in Mayavaram in 1932. SNN’s eldest son KS Narayanan (KSN) joined the bank in 1936, gaining experience while moving from branch to branch. He also became a close friend of TS Narayanaswami (TSN), who was with the bank. The two enjoyed a warm working relationship till Narayanaswami passed away in 1968. By then, they had moved beyond banking.

In fact, KSN moved earlier. In the late 1930s, he was Madras-bound to shepherd a failing ink manufacturing unit, Nanco, that had been acquired. By 1941, it was a success. With a War on, he next turned to a commodity in short supply, rubber, acquiring a re-treading unit in Coimbatore. There followed the first foray into chemicals, a sick unit there making calcium carbide, Industrial Chemicals, being taken over.

Meanwhile, SNN who had bought substantial acreage in Tinnevelly to farm, found it was limestone-rich. His thoughts turned to cement. And so was born India Cements in 1949, with Narayanaswami helping SNN set it up while KSN went to Denmark to train with cement major FL Smidth. At a time when India was yet to industrialise, this was a major venture. When TSN died, KSN headed India Cements till retiring at 60, in 1980.

Why KSN and TSN decided to get into chemical products we’ll never know, but in 1962 they thought of manufacturing PVC. TSN went to the US and negotiated a joint venture agreement with BF Goodrich, a PVC major. Agreement led to starting Chemicals and Plastics India Ltd in Mettur, near Mettur Chemicals which would supply the necessary chlorine. The plant went on stream on May 4, 1967, the date the Golden Jubilee celebrations recalled. This was one of the first Indo-American joint ventures, also among the first with a multinational in South India. The story only grows from thereon.

*****

The death of a trainer

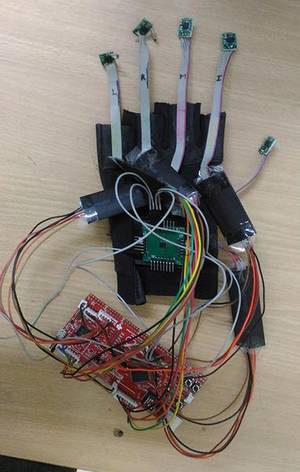

Few knew him outside the two worlds he’ll sorely be missed in, those of printers and Salesians. They merged for Bro Julian Santi, who passed away recently, in the Salesian Institute of Graphic Arts he set up in Kilpauk in the late 1960s with help from friends and Salesians in Italy from where he arrived in 1957.

We first met years later and, even after, it was infrequently, but for over 40 years I would meet ex-students of his. And they were generally a class apart. Most of us printers, and several abroad, preferred them when recruiting, because they came with two advantages: More machine experience than those from other printing schools, and they considered themselves craftsmen, not ready-made white collar supervisors, which many from elsewhere thought they should be because they’d got a few letters as suffixes. Training on the job and a strong work ethic, that a printer had to be a hands-on person, not necessarily a whiz in theory, was what Santi taught his wards. Few of our training institutions look at students that way.

Was Santi a printer himself, was he SIGA’s Principal, I never discovered, but I did find out he was a trainer par excellence, a man who taught his wards the dignity of working with their hands. I hope he has rooted that culture deep in SIGA.

*****

When the postman knocked…

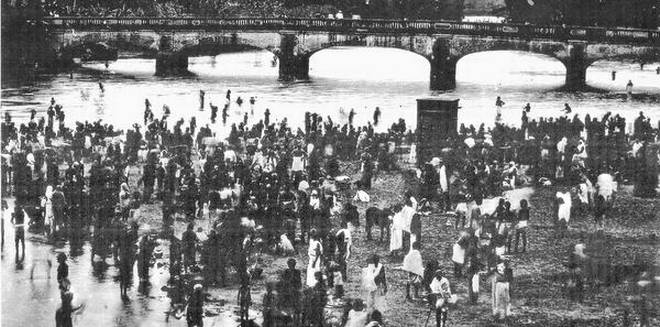

Several items over the last six weeks have brought much mail and, happily, several noteworthy pictures. They’ll appear over the following weeks, one at a time, starting today to supplement the earliest, Marmalong Bridge.

DH Rao for whom bridges, lighthouses and the Buckingham Canal are passions, sent me today’s picture. Rao had seen it at a Corporation of Madras exhibition where it was dated to 1900. Its caption added, “In 1966 it was dismantled and replaced with today’s bridge.” The caption also said that a plaque was removed and re-positioned at the bridge’s north end. That plaque, recalling Uscan’s contribution, is little cared for today and is almost hidden by road-raising.

Rao adds he came across the following, written in 1829, by a French naval officer, J Dumont D’Urville: “An entire neighbourhood is reserved for Muslims and we go there by the Armenian bridge (Saidapet?) built on the river Mylapore. This bridge 395 metres in length (has) 29 arches of various sizes.”

The chronicler of Madras that is Chennai tells stories of people, places and events from the years gone by, and sometimes, from today.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> Madras Miscellany / by S. Muthiah / May 15th, 2017