Madurai :

The three km narrow road to Keelakuyilkudi village from the Madurai – Theni highway is unusually winding. “It was a deliberate design by our ancestors to delay British policemen from reaching the village quickly,” says Pon Harichandran, a villager.

By the time British forces negotiate the curves, messengers atop Samanarmalai would signal villagers who would prepare to take on the policemen. Keelakuyilkudi, now an agrarian village, was one place that gave nightmares for British until they left India, thanks to the militant clan of villagers belonging to ‘piramalai kallar’ community. It was to tame them British enforced the draconian Criminal Tribes Act (CTA), 100 years ago.

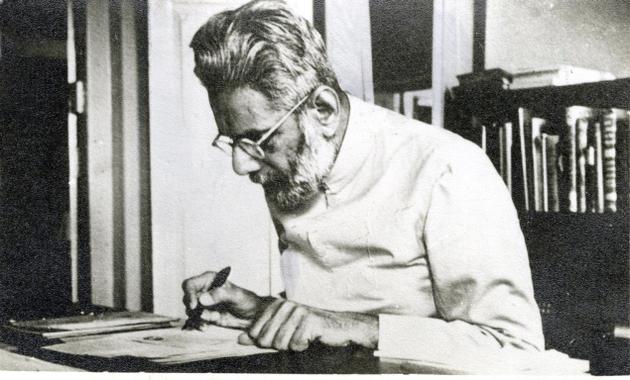

Keelakuyilkudi was the first village in Madras Presidency where CTA was enforced. “It was 1914, three years after CTA was extended to Madras Presidency, the British cracked down on Keelakuyilkudi villagers,” says Su Venkatesan, whose Sahitya Akademi award winning debut novel ‘Kaaval Kottam’ dwelt in detail about the Act. The villagers have organised a three-day meet from May 5 to mark the centenary of CTA.

According to CTA, the males of a village right from adolescents to aged should appear in the nearest police station and leave their fingerprints every evening and morning. This was to restrict their movement and ensure that they do not go on a burgling spree. Of the 600-odd males of Keelakuyilkudi, more than 350 men were under the ambit of CTA. But Harichandran said that even before CTA was enforced in 1914, all men from Keelakuyilkudi were taken to police station and forced to stay there every night.

The villagers used to go to Tiruparankunram police station, eight miles away twice a day to leave their fingerprints. Though villagers admit that there were instances of theft by Keelakuyilkudi men, they were later given the job of guarding Madurai due to their valour. “But when they were refused payment for guarding the city, a common man from Keelakuyilkudi took on a senior British police officer which provoked them to enforce the law,” Harichandran says.

A Veemarajan (71), a descendent of CTA victims, says whenever something was stolen in any part of Madurai, police would swoop down only on Keelakuyilkudi. “Police would enter into our house anytime and arrest anyone without a warrant,” he said.

“Neighbouring villagers would not speak to us fearing police action,” he said. Peeliyamma (70) says during her marriage, many expressed concern why she chose a man from Keelakuyilkudi.

Later, the Act was extended to Urappanur and Perungamanallur villages also. It was at Perungamanallur 16 villagers including a woman were shot down by British for resisting the Act in 1920.

As resistance of the Act continued, British established a permanent police post in Keelakuyilkudi. A munsif court and a jail were also established. “Twice in a week, a munsif would visit the court and settle the cases,” a villager recalls.

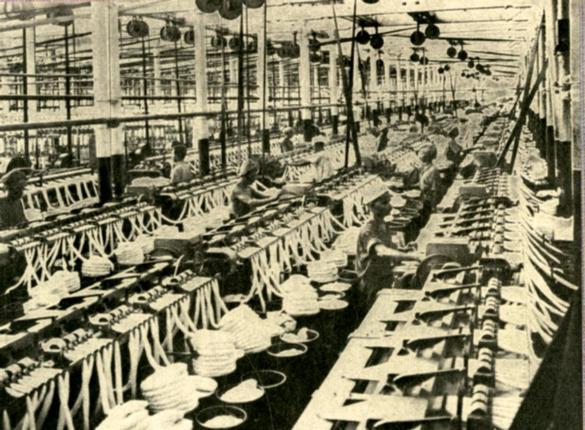

Simultaneously, the British also set up a handloom unit, opened a school, the first girls school in the state and even a bank to provide loans for pursuing alternative means of livelihood. But the villagers resisted everything that was British.

The Act was finally repealed after independence in 1949. The dilapidated building that housed the munsif court stands a silent testimony to the harrowing past of the village.

source: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com / The Times of India / Home> City> Madurai / by V. Mayilvaganan, TNN / May 05th, 2014