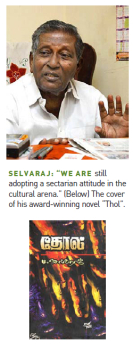

S. DORAIRAJInterview with D. Selvaraj, winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award. D. Selvaraj in a tannery in Dindigul. “When class struggle sharpens, automatically, caste struggle will merge with it.” Photograph by S. James“[A]mong the younger leftist writers, D. Selvaraj is sometimes quite successful in depicting the life of the proletariat, especially of the Pallar agricultural labourers.”

D. Selvaraj in a tannery in Dindigul. “When class struggle sharpens, automatically, caste struggle will merge with it.” Photograph by S. James“[A]mong the younger leftist writers, D. Selvaraj is sometimes quite successful in depicting the life of the proletariat, especially of the Pallar agricultural labourers.”

—Kamil Veith Zvelebil

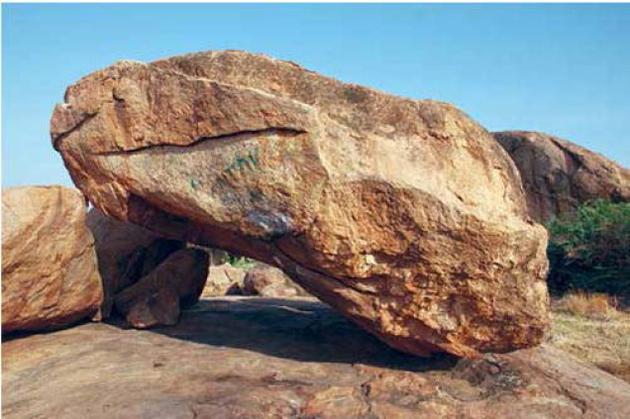

Almost four decades have rolled by since the world-renowned Czech Tamil scholar Zvelebil made his assessment of writer Daniel Selvaraj’s contribution to modern Tamil literature in his famous work A History of Indian Literature published in 1973. Selvaraj’s novel, Thol (Hide), which speaks about the travails and struggles of the Dalit tannery workers of Dindigul in the composite Madurai district from 1930 to 1958, has been chosen for the Sahitya Akademi Award for 2011. The novel has already won the Tamil Nadu government’s award for 2010.

The relevance of the novel can be gauged from the fact that primitive methods of processing hide is witnessed even today at some tanneries in Dindigul and in several other factories workers face occupational risks.

Ever since he entered the world of literature, Selvaraj has been unswervingly moving along the path of Marxism and socialist realism, steering clear of attempts to classify his works as Dalit literature. Almost all his creations highlight the plight of the workers and the toiling masses and their consistent struggle for changing the social order.

The 74-year-old writer’s first novel, Malarum Sarugum (Flower and dead leaf) revolves around the peasants’ struggle against landlords who deceived tenants by using unauthorised measures. The novel was published in 1967. His second novel Theneer (Tea) came out in 1973. It deals with the appalling living and working conditions of the tea estate workers. Mooladhanam (Capital) and Agnikuntam (Fire pit) were published in 1977 and 1980 respectively. Of these, Mooladhanam highlights issues such as collapse of the joint family system and authoritarianism while Agnikuntam is about problems in the judiciary.

Much before writing novels, he started writing short stories. Many of his 200-odd short stories have appeared in reputed literary and political journals, including Santhi, Saraswathi, Thamarai, Semmalar, Sigaram, Janasakthi and the Sri Lankan Tamil weekly, Desabimani.

He has authored the biographies of Communist leader P. Jeevanandam and Tamil scholar Sami Chidambaranar. He has also penned two stage plays, Paattumudiyum Munne and Yuga Sangamam, and more than 30 one-act plays. His novels are part of curriculum in some universities and also taken for research projects.

Born into a family of tea estate workers and Kanganis (labour contractors), Selvaraj studied law. The practising lawyer says that his profession also contributes to his writing as he has to meet clients with different problems. His in-laws were freedom fighters. His wife Bharataputri was born in jail. Even while balancing between his profession and writing, the novelist loves spending time with his grandchildren at his Dindigul residence.

In this interview to Frontline, Selvaraj discusses issues, including the path which led him to the world of literature, his unshakable faith in socialist realism, the need to synchronise class struggle and caste struggle and the need to conduct field work before writing novels. Excerpts:

The Sahitya Akademi award has come to you nearly five decades after you embarked on your literary journey. Do you think this is a belated recognition?

Even when I was a student of the M.D.T. Hindu College in Tamil Nadu’s Tirunelveli town in the late 1950s, I was guided into the world of progressive literature by three acclaimed literary persons: T.M.C. Ragunathan, the great Tamil poet-cum-novelist; N. Vanamamalai, outstanding Tamil scholar who enabled researchers to adopt the Marxist approach to literary analysis; and T.K. Sivasankaran, well-known critic.

There was a time when Sahitya Akademi was dominated by persons who believed in the theory: art for art’s sake. As a writer who always holds the view that art is for social purpose, I did not expect the academy to have any proper appreciation of progressive writing in the then prevailing scenario.

However, the situation underwent a gradual change, thanks to the role played by progressive cultural organisations such as the Tamil Nadu Kalai Ilakkiya Perumanram (Tamil Nadu Federation of Art and Literature) and the Tamil Nadu Murpokku Ezhuthalarkal and Kalaignarkal Sangam (Tamil Nadu Progressive Writers and Artists Association).

This is evident from the fact that Sahitya Akademi awards have been conferred on progressive Tamil writers in the recent period. Though as a writer, Akademi’s award has come to me belatedly, in the case of Thol it is not late, as the novel was published only a couple of years ago.

“Thol” revolves around the life and struggle of the tannery workers, who by and large are Dalits. Can you recall the circumstances under which you ventured into the work?

It all started in the early 1960s when I was studying law in Chennai. I was closely associated withJanasakthi, the official organ of the Tamil Nadu unit of the undivided Communist Party of India. I also developed contacts with leaders of the trade union movement. During that time, veteran trade unionist and former Mayor of then Madras Corporation S. Krishnamurty helped me to familiarise myself with the problems of the tannery workers who were living under the most appalling conditions in Chromepet on the outskirts of Chennai. He also briefed me on the outrageous working atmosphere in the tanneries of Dindigul, which was part of the composite Madurai district then.

As a concomitant development, S.A. Thangaraj, one of the founder-members of the tannery workers’ union, asked me to come to Dindigul to help the union as a lawyer in its struggle for enhanced wages and better working conditions. Accepting his invitation, I came to Dindigul in 1975.

Even while handling several cases pertaining to the problems of the tannery and municipal workers, as a writer I wanted to portray the oppressions faced by them socially, economically and politically. This is how I ventured into writing the story of the tannery workers of Dindigul and their heroic struggles.

You must have done a lot of field study before writing Thol?

The first thing I did after coming to Dindigul was to undertake visits to the hamlets and colonies of the tannery workers and municipal employees with a view to studying their life and family background. They had rallied under very strong unions. Frequent interactions with the workers, more particularly the veterans who had actually participated in the struggles, enabled me to get a useful feedback on their conviction and loyalty to the union in the face of police repression.

Further to understanding the life of their leaders, I went through the life history of a number of communist stalwarts, including P. Ramamurthy, A.S.K. Iyengar, M.R. Venkatraman, A. Balasubramaniam, V. Madanagopal and K.P. Janaki. Though I had Balasubramaniam in mind when I created the leading character of the novel, Sankaran, he was the combination of the unique qualities of all these leaders. It took around 20 years for me to complete Thol.

Did you adopt the same strategy for other novels also?

I did not resort to much field work for Malarum Sarugum, which was based on the historic Muthirai Marakkal struggle of the small peasants and their life, as the story was set in my native village Thenkalam in Tirunelveli district. I was a college student then. During the vacation, I used to interact with the farmers in my village and elicited details on the struggle.

As far as Theneer is concerned, it runs in my blood. I was born into a family of Kanganis who brought labourers from Tamil Nadu to work in the tea estates in Kerala. More than 300 workers were in their gang. A percentage of the wage earned by the worker would go to the Kangani as commission. The system was in vogue in the colonial era.

It may sound odd but nevertheless it is true that tea estates in the entire Devikulam area in the princely state of Travancore, presently in Idukki district, were under the control of the British planters. It was like an impenetrable island without any means of communication and people in the estate did not even know the advent of freedom to India.

I studied in the Munnar High School, which was exclusively run for the children of the Kanganis and staff members of the estate. The medium of instruction was English. Mostly those who finished the school final examinations were absorbed as staff by the company. I was one of the few boys who were able to move out the district and got a degree in Tamil Nadu.

My association with the estate workers right from my school days enabled me to gain first-hand knowledge about their problems.

It has been my firm opinion that conducting field study is very important for a serious writer. By doing so he is able to see the life of the people for whom he writes, besides understanding their inner feelings and gauging the overall situation through lively interactions with them. Almost all the characters in my novels including the ones in Thol are based on real people and they are not purely imaginary.

What kind of satisfaction do you draw from “Thol”?

In fact, I did not make any attempt to get the novel published, as the manuscript ran to more than 2000 pages. But when the New Century Book House came forward to publish it, I rewrote the entire novel.

I can say with confidence that at least for the next 10 years no other writer would write such a novel, which chronicles the struggles waged by the workers and peasants in the State from 1930-1958.

Though the CPI was outlawed during that period and its leaders went underground, they were able to effectively organise the working class and peasantry especially tannery, textile, handloom and municipal workers and peasants. They had also successfully synchronised the struggle against caste oppression with class struggle. Even today, this remarkable feature is worthy of emulation after subjecting it to a thorough analysis.

I treat the Sahitya Akademi Award for my novel not as a personal achievement but as a recognition to these historic struggles launched by the communist and trade union movements during that period.

It is said that many of the 117 characters in the 700-page novel are real-life heroes. How do you evaluate the role of the leaders who worked for the cause of the toiling people then?

In those days, the tannery workers and municipal workers were treated as outcasts and they were not allowed to enter Dindigul town. Their colonies were segregated in such a way that the wind blowing across these habitations would not touch the town. But the communist leaders reached out to them, lived with them and organised them.

The greatness of the leaders like A. Balasubramaniam, who was born into an orthodox Brahmin family, lies in identifying themselves as declassed and adopting the food habits of the tannery workers to help them develop class consciousness and take a plunge not only in the struggle for better wages but also in the freedom movement. V. Madanagopal was an equally important leader who worked among the tannery workers and faced brutal police repression. I have recorded the sacrifice of such leaders in my novel.

Literary works centring round the life and struggles of the toiling people and their leaders are dubbed propaganda literature. Would you like to comment?

Frankly speaking, all my works can be classified as propaganda literature. But when the writer resorts to faithful description of life, his works will not appear to be propaganda. It has also been said that the characters in Tolstoy’s monumental work War and Peace are the combination of historical figures of the Napoleon era and the imaginary characters of the ancient Greek poet Homer. I have adopted this technique in my novels.

Who is your role model?

It is true that the early inspiration came from the works of Guy de Maupassant and Charles Dickens. In my earlier days of writing, I took Pudumaipithan and Ragunathan as my role models. Then assimilating the styles of Maxim Gorky, Krishan Chander and Thakazhi Sivasankaran Pillai, I evolved my own style of writing.

Can you recall your association with stalwarts of the progressive writers’ movement in Tamil Nadu?

My association with Ragunathan, Vanamamalai and Sivasankaran is unforgettable. They revaluated the ancient Tamil literature in a scientific and Marxist way. They started the Tirunelveli Progressive Writers’ Association. With utmost devotion they trained me and my contemporary Sundara Ramaswamy. We embarked on our literary journey by contributing to Santhi, a literary journal edited by Ragunathan. Among my contemporaries are Jayakanthan and Krishnan Nambi.

When I joined the Madras Law College, I had close association with P. Jeevanandam, the great orator and communist leader. A special quality of these literary giants was that they were not only unassuming but also treated their comrades as equals. Another leader who had amazingly deep knowledge of English literature was A.S.K. Iyengar, doyen of the trade union movement in Chennai. Tamil Oli, a poet par excellence, pioneered portrayal of the pathetic life of the oppressed sections.

There is a view that the progressive cultural movement in the country has lost its sheen. Can it still galvanise democratic-minded writers and artists?

Though communists and pro-communists took the lead in organising the All India Progressive Writers’ Association in 1936, it was able to galvanise democratic-minded writers and thinkers including Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Abdul Kalam Azad and Sarojini Naidu. But this had not happened in Tamil Nadu, though an attempt was made in the State with Janasakthi offering space for non-communist writers and thinkers. The progressive writers’ movement ought to have brought into its fold humanists and realists.

Unfortunately, we are still adopting a sectarian attitude in the cultural arena. This approach continues even after the formation of the Tamil Nadu KalaiIlakkiya Perumanram, Makkal Ezhuthalar Sangam and the Tamil Nadu Progressive Writers and Artists’ Association.

In my opinion, still there is scope for the progressive writers’ movement to re-induct democratic-minded thinkers and writers. As a cultural vacuum is rapidly developing in the State, the Left and progressive thinkers and writers have the great task of tackling this lurking danger.

Is it true that socialist realism has become obsolete after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist camp?

I don’t think that socialist realism has become obsolete. Thol is living proof of the relevance of socialist realism, which cannot be replaced by any other ‘ism’. Magical realism may be relevant to Latin America, which was under the oppression of the United States.

Post-modernism is only a perverted understanding of life. But socialist realism is dialectical, which sees the transformation in individuals, society and nature. It is a scientific approach.

Certain Dalit thinkers treat ideology as a fetter, which comes in the way of writers wielding their pen against caste oppression. Do you agree with this point of view?

Such anarchic views arise because most of the Dalit writers are middle-class intellectuals. Through their writings, they highlight issues such as social oppression, sufferings and insults heaped on Dalits. They never try to move beyond that purposely. They refuse to depict the struggles of Dalit people to liberate themselves and organise themselves into a trade union movement. In fact, such caste associations help the hostile forces to effortlessly create a deep schism among the working class and the peasantry. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes form one-third of the Indian population. Indian community cannot move forward or will it be able to change the social order if these oppressed people were prevented from taking part in common struggles for transformation.

So, unity between Dalits and non-Dalits is essential to ensure the liberation of the oppressed people, ending the prevailing social order. Such a synchronisation of class and caste was successfully achieved by the communist and trade union movements before 1958 in Tamil Nadu. That has to be studied in detail for future action.

Don’t forget that caste itself is the creation of class. When class struggle sharpens, automatically, caste struggle will merge with it. But even after attaining socialism, the remnants of the old order may continue for some time before getting abolished completely. That is the dialectical and historical process which we can’t predict today.

In this connection, I would like to say that we cannot equate Dalitism with postmodernism. I am optimistic that in the course of time, Dalitism will accept socialist realism and become part of it.

Some people even argue that Dalit writers alone can understand the intricacies of Dalits’ problems…

This is absurd. Any writer, who observes changes obtaining in a society, can write about the travails undergone by any person. If you extend the same logic, a Dalit writer should not portray the problems of women or children.

If you go further, it may even be argued that nobody other than a child can write about the problems of the children.

source: http://www.frontline.in / Home> Literature / Volume No. 30, Issue 01, Jan 12-25, 2013 / by S. Dorairaj /