Connemara Library opens its older section, which stores rare books, to book lovers in the city once a year during World Book Day week.

Chennai :

It’s that time of the year when the older section of Connemara Public Library opens its door for the public — starting from World Book Day on April 23 until today. The searing heat does not stop people from dropping in and catching a glimpse of the preserved legacy, their rare book collection and the stunning architecture. Currently, the old section is used for storing rare books. It’s restricted to public but books can be accessed by scholars, researchers or students on request and can be read from the reception room.

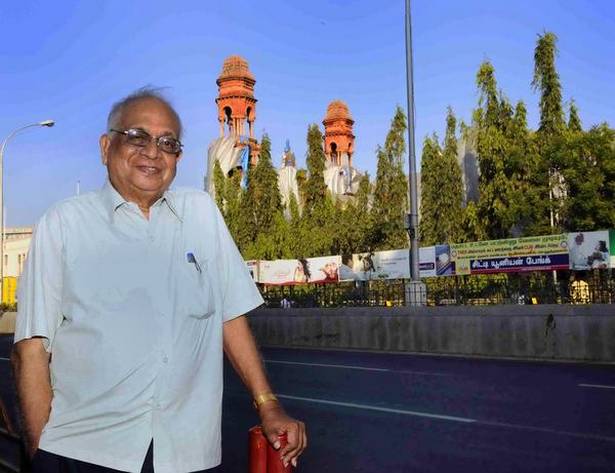

There’s a red carpet path connecting the newer section to the older one. Ornate teak furniture, stained glass windows, vibrant patterns on the ceiling, arches engraved with sculptures and stacks of age-old books add to its beauty. The library was formally opened in 1896 to the south of Madras Museum, culminating in the museum theatre at the head of the campus. It is said to be named after Lord Baron Connemara, then Governor of Madras Presidency.

Past glory

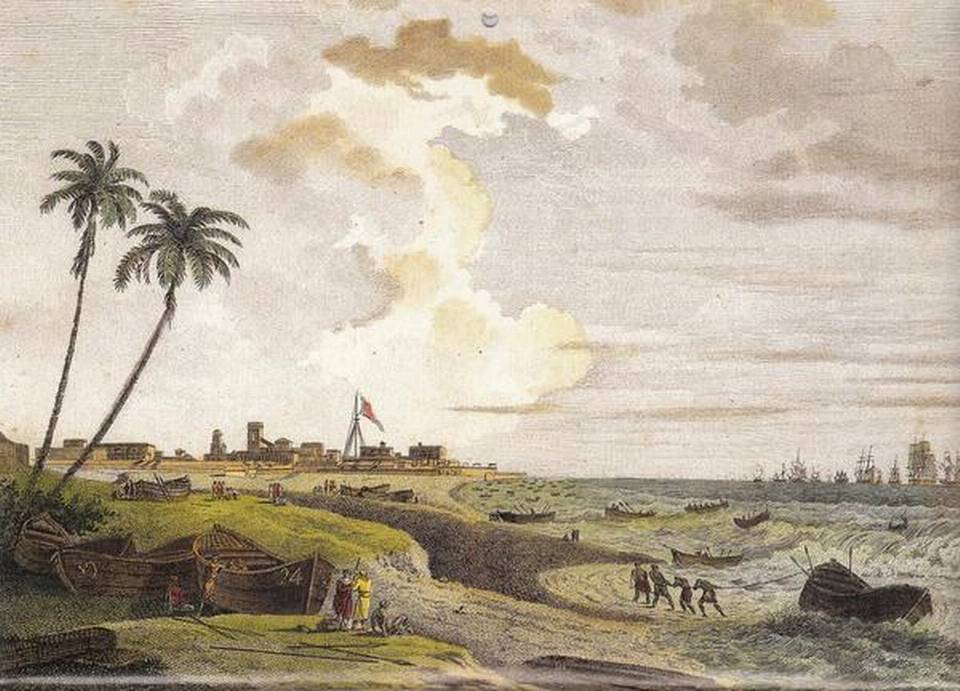

The Madras Museum comprises numerous old buildings within its compound, and this library is one among them. The entire complex gains entry from Pantheon Road, which takes its name from the historic pantheon or public assembly rooms. References to the assembly room occur in 1789, a time when the city wanted a theatrical entertainment. Actively used in the latter part of 18th century, the government acquired the property in 1830 and established the Collector’s Cutcherry before the central museum in 1854.

Earlier, it had a single-floor high structure with two halls and a room for orchestra. The pantheon still exists. Two large wings with an upper floor are believed to be added when it was converted into a museum with further additions between 1886 and 1890. The space is said to have contained grooves in the roof over the stage to roll cannon balls to stimulate the sound of thunder. This structure is now a part of the two-floor old museum block, rear of the Connemara library.

Ageless charm

“What we see now is with later additions which are intricate and have a lot of details in terms of the stained glass or the teak finishes or the wooden brackets in the chambers. It has gone through four different purposes and the elements were added during consecutive additions. It’s an important part of Madras and a landmark that Chennai should be proud of,” said Thirupurasundari Sevvel, who conducted the trail as part of Nam Veedu Nam Oor Nam Kadhai. No two patterns in the stained glass windows are the same. It is said that the colours from the window reflect on marble floors at dusk.

The library benefitted from the Madras Literary Society on College Road — Fort St George campus — from where the Geology books were brought here. “We’ve displayed 300 books — from paintings to literature. Last year the library witnessed 2,000 people during public access. This year it’s open for five days. The count has crossed 1,000 in just two days.

The awareness has increased,” said a library staff. Considering its national depository, the library is entitled to get a copy of any book published by any publication in the world. The library is accessible for people with special needs. A walk around the space will not only expose you to the grandeur of the interior decor but also its treasured collection. The older section of Connemara Public Library is open until today from 10 am to 5 pm.

source: http://www.newindianexpress.com / The New Indian Express / Home> Cities> Chennai / by Vaishali Vijayakumar / Express News Service / April 27th, 2019