Meet the man who has devoted his life to saving some of those now-famous native cattle breeds in his farm in the heart of Tamil Nadu.

A dappled calf saunters up. I offer it my hand. It nuzzles and then proceeds to lick it. Another joins it, and yet another. I am enjoying the attention — until a sudden tug distracts me. A tiny mouth has just begun nibbling the tassels of my cotton dupatta. I beat a hasty retreat, almost landing ankle-deep in a mound of steaming dung.

Ganesan laughs and pats the head of the calf that has just tried to eat up my dupatta. “This calf belongs to the Gir breed,” he says, drawing my attention to the convex forehead and pendulous ears distinctive to the breed whose origins lie, as the name suggests, in the Gir forest region of Gujarat.

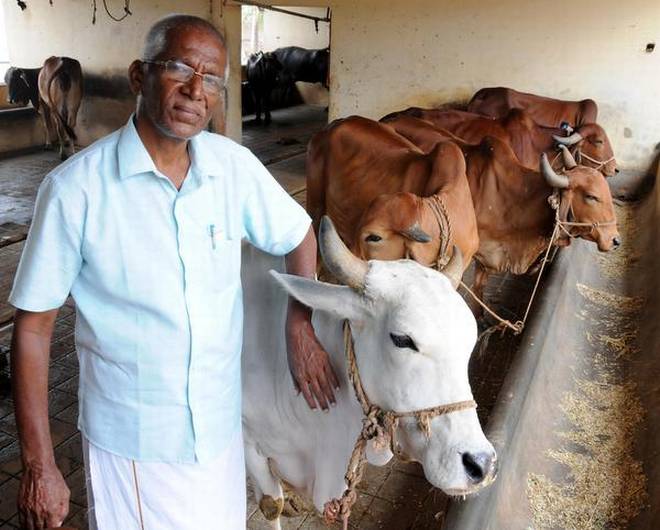

C. Ganesan is a slender, bespectacled man, wearing a dhoti, blue shirt and ready smile. He runs what he calls an “experimental farm” in P. Chellandipalayam in Karur district of Tamil Nadu, the state that exploded with the jallikattu protests some weeks ago. Among the arguments extended by the fans of this rather cruel bull race was that native breeds of cattle could be protected through the sport. Experts spoke of how Indian cattle had vanished and of the higher nutrient content in the milk of these cows.

Despite the argument, the truth is that most cattle raised for dairy farming in India is imported from abroad. Since these breeds are reported to yield much higher quantities of milk, they are found more suitable for commercial use.

The road that leads to Ganesan’s farm is a kaccha, vertigo-inducing path flanked by arid, patchy coconut groves, rust-coloured rocks, and acres of barren paddy fields. Thorny scrub give way to worn fences but they offer scant protection from the marauding peacocks, complains Ganesan, “I really need to fence these fields properly,” he says with a shrug.

Ganesan set up his farm some 13 years ago to prove that Indian breeds can give high yields of milk, more than 15 litres a day: “My cows produce copious quantities of milk and like all other local breeds have excellent immunity.” His farm has only indigenous breeds. Besides Gir, there is Sahiwal and Tharparkar (named after the Pakistani towns of their origin), a few buffaloes, the local Kangayam breed, and a few head of Thalacherry goat.

Ganesan’s family also owns a textile business but farming is in their blood. “Agriculture is our ancestral occupation and we have been keeping cattle for a long time,” he says. Earlier, the genial farmer’s animals were Jersey cross-breeds. “The government recommends a mix of 65% Jersey with 35% native breed of cattle, but this is hard for farmers to maintain,” he explains. “Proper breeding management doesn’t happen in India.”

Then, in 2003, he lost five Jersey cross-bred cows very suddenly, “They have poor immunity and one had to keep replacing them,” he says. That’s when he began to convert exotic cross-breeds into desi. “I purchased a few desi animals — around 10 Tharparkar cows. Also, I began inseminating my Jersey cross-bred cows with semen samples taken from pure Indian breeds.”

There are over 50 heads of pure Indian cattle on his farm now — of various colours, shapes and sizes. A newly born calf totters up as we approach while its mother fixes us with a steely gaze and lowers her horns. Pitch-black buffaloes swill down water and bellow; red and white cows stick their heads into feeding troughs; gambolling calves behind wire-netting peer curiously at us.

“The easiest way to identify a desi breed is by the hump,” says Ganesan. And yes, all humped cattle produce milk rich in the much-touted A2 milk protein. A2 milk is excellent for children, he says, adding that it helps brain function and promotes growth. The fodder, culled from the fields around him, does not have pesticide and unlike commercial establishments he does not inject his cows with oxytocin injections to induce lactation, “My grandchildren refuse to drink any other milk or curd,” he laughs, as he leads me into his sparse office where a hot cup of tea made with freshly-drawn milk awaits.

Milk, however, is only a by-product of Ganesan’s experiment, “This is not a commercial farm — it is only a model one,” he says, explaining that he sells his milk at the ridiculously low rate of ₹30 per litre, “It must be the lowest rate in Tamil Nadu,” he grins. But the milk reaches his customers within two hours of milking.

What Ganesan really wants to prove is that native Indian breeds are more than capable of producing milk on a commercial scale. “The government doesn’t work at improving their milk capacity. Even breeds like Kangayam, which are not traditionally bred for milk, can produce up to six litres a day if the breeding is done properly.”

According to him, the best sort of cattle comes from artificial insemination done right. Getting high quality semen samples can be challenging. Ganesan currently gets his frozen samples from the National Dairy Development Board. “Once we get good animals, the milk is automatically better.”

And what role can jallikattu play in preserving desi breeds, I ask. “Those bulls are not really used for breeding — they are trained to be ferocious,” he says, and adds, “Anyway, jallikattu is not about preserving local breeds, it is about men proving themselves.”

preeti.z@thehindu.co.in

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> History & Culture> Cattle Class / by Preeti Zachariah / February 04th, 2017